Sliman Bensmaia, whose pioneering work on the neuroscience of touch opened doors for amputees and people with quadriplegia, allowing them not just to grasp a cup of coffee, for example, but to feel its heat and know just how much pressure to apply to hold it tightly, died on Aug. 11 at his home in Chicago. He was 49.

His death was confirmed by the University of Chicago, where he was a professor in its department of organismal biology and anatomy. No cause was given.

Dr. Bensmaia was a postdoctoral fellow at Johns Hopkins University in the 2000s when the Defense Department, faced with a mounting number of wounded veterans returning from Afghanistan and Iraq, committed $100 million to prosthetics research.

Scientists were making enormous strides in the field of brain-controlled prosthetics, but giving users of such devices a sense of touch was still largely uncharted territory. Patients could not actually feel what they were doing: whether a material was rough or smooth, if it was moving or stable, even where their limb was in space.

Dr. Bensmaia (pronounced bens-MAY-ah) saw his task as taking the next step: understanding how the brain receives and processes information through touch, which in turn could allow prosthetics to perform more akin to an organic limb.

“Touch is so rich, so multidimensional,” he told Discover magazine in 2016. “There’s a lot we do understand, but there’s still a lot we don’t know.”

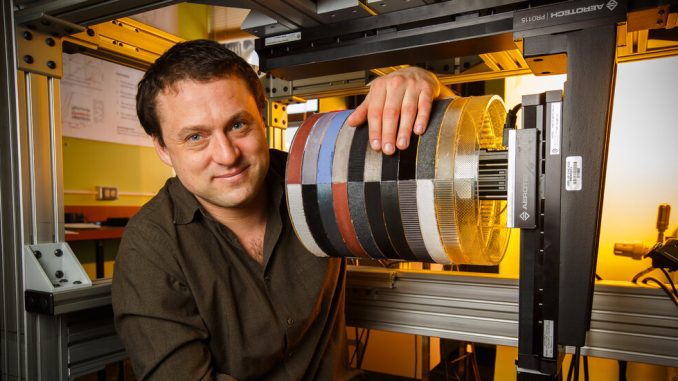

Much of his basic research involved rhesus monkeys, whose neural systems closely resemble those of humans.

He and his team would connect electrodes to areas of the monkeys’ brains, poke spots on their hands and then analyze where the brains received that sensory information, as well as how the animals reacted. They then used electrodes to simulate those pokes, in an attempt to mimic the experience.

“When you imagine moving your arm, that part of the brain is still active, but nothing happens due to the lost connection,” he told the magazine Wireless Design and Development in 2014. “The idea behind the project was to stick electrodes in the brain and stimulate it directly to produce some percepts of touch to better control the modular limb.”

Most scientists focus their labs on either pure or applied research. Dr. Bensmaia’s group — some two dozen undergraduates, grad students, postdocs and technicians — managed to do both. He employed neuroscientists, but also teams of engineers and computer programmers.

“He ran his lab like a small company,” David Freedman, a neurobiologist at Chicago, said in a phone interview.

Such coordination was necessary for the complicated work Dr. Bensmaia engaged in. The sense of touch involves a wide array of finely measured inputs — pressure, heat, movement, hardness — all of which are communicated to the brain through some 100 billion neurons and 100 trillion synaptic connections.

“The hand, in a way, is an expression of our intelligence, our neural sophistication,” he said in 2022 on a podcast with Mark Mattson, a neuroscience professor at Johns Hopkins University.

A talented pianist who played regular gigs around Chicago, Dr. Bensmaia compared the flush of inputs to a “neural symphony.”

He took his research from Johns Hopkins to the University of Chicago in 2009, but continued to collaborate with his former colleagues at Hopkins, as well as research teams at the University of Pittsburgh.

In 2016, his team and a group from the University of Pittsburgh outfitted a 28-year-old man, Nathan Copeland, who had been paralyzed from the neck down, with a prosthetic arm that allowed him to feel through its finger tips.

During a visit to the lab, President Barack Obama watched Mr. Copeland in action, then gave him a fist bump.

“That is unbelievable,” Mr. Obama said.

Sliman Julien Bensmaia was born on Sept. 17, 1973, in Nice, France. His parents, Reda Bensmaia and Joëlle Proust, are philosophers. Sliman grew up in France and Algeria, then moved to the United States at 15.

He studied cognitive science at the University of Virginia, with a plan to go into music. But his parents persuaded him to pursue a doctoral degree instead, so after graduating in 1995 he enrolled in the cognitive psychology department at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. He received his Ph.D. in 2003.

Dr. Bensmaia was a prolific researcher; he and his colleague Stacy Lindau had recently begun work on a bionic breast, to restore sensation to patients after mastectomies.

In addition to his parents, Dr. Bensmaia is survived by his wife, Kerry Ledoux; his brother, Djamel; and his children, Cecily and Maceo.

Dr. Bensmaia never lost his interest in music: He and Dr. Freedman, his colleague at Chicago, formed a band, FuzZz, and even released an album in 2013.

But it was only in the last few weeks that the two had begun talking about conducting a research project together, on the relationship between how the brain processes visual and touch inputs.

Be the first to comment