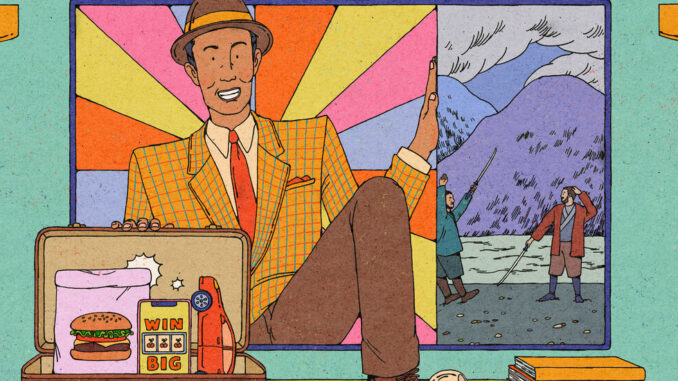

Not long ago, streaming TV came with a promise: Sign up, and commercials will be a thing of the past.

Netflix rose to streaming dominance in part by luring customers to an ad-free experience. Amazon Prime Video, Disney+ and HBO Max followed that lead.

Well, that did not last long.

Ads are getting increasingly hard to avoid on streaming services. One by one, Netflix, Disney+, Peacock, Paramount+ and Max have added 30- and 60-second commercials in exchange for a slightly lower subscription price. Amazon has turned ads on by default. And the live sports on those services include built-in commercial breaks no matter what price you pay.

The importance of advertising was driven home this month when Amazon and Netflix both staged their first in-person presentations during the so-called upfronts, a decades-old television event in New York where media companies try to woo advertisers.

Netflix dispatched Shonda Rhimes, the successful executive producer of “Bridgerton” and creator of “Grey’s Anatomy,” to talk up the service to marketers. Amazon packed its event with celebrities like Reese Witherspoon and Jake Gyllenhaal, and a live performance from Alicia Keys.

“Remember when streamers told you, ‘We’re going to do television a new way, so I’m afraid we won’t be needing your little commercials anymore,’” Seth Meyers, the “Late Night” host, told advertisers at one of the events this month. “Cut to a few years later, every episode of ‘Shogun’ is interrupted by ‘Whopper, Whopper, Double Whopper!’”

Or as one frustrated consumer vented on social media this past week: “Why am I paying for Prime Video and getting all these commercials? It is beginning to get annoying.”

Representatives for Netflix and Amazon declined to comment.

Perhaps the changed viewing experience was inevitable. Over the last decade, as media companies raced to introduce streaming services to compete with Netflix, they prized subscriber counts above all else.

There was just one problem: profits.

The companies bled money, and Wall Street soured on their businesses. So executives are turning back the clock. They are ordering lower-cost, old network standbys like medical dramas, legal shows and sitcoms. They are offering bundled packages to make consumers less tempted to click on the cancel button. (Disney+, Hulu and Max will team up later this year, for instance.) And they are embracing commercials, as a way to increase revenue.

“The crazy thing is that we might wind up where we’re back to ‘Texaco Presents,’” said Chuck Lorre, the comedy hitmaker behind shows like “Young Sheldon,” “Two and a Half Men” and “The Big Bang Theory.” “I’m old enough to remember Fred and Barney on ‘The Flintstones’ smoking cigarettes because the show was paid for by a tobacco company.”

Consumers can still avoid most of the ads, for a price. Most streaming services still have an ad-free version, including Amazon, which requires subscribers to pay an extra $3 a month to skip the ads. Apple TV+ continues to offer only an ad-free experience.

The commercial tiers, however, are becoming more essential to their business. There were at least 93 million ad-supported streaming subscriptions in the United States at the end of last year, according to estimates from Brian Wieser, an industry analyst, and Antenna, a subscription research firm. In the wake of Amazon’s automatic switch to advertising, and more ad-tier customers picked up by other streaming services, Mr. Wieser and Antenna estimate that there are at least 170 million ad-supported subscriptions now.

Through the first three months of 2024, 56 percent of new subscribers to a streaming service chose the lower-priced ad-tier, according to Antenna. That was up from 39 percent a year earlier, the firm said.

Executives have tried to assure subscribers that while advertising is back, it won’t be as overwhelming as in traditional television.

Just a few years ago, an episode of a prestige basic cable drama like Ryan Murphy’s “American Crime Story” was interrupted by 21 minutes of commercials. But ads take up far less time on streaming services. For instance, on Disney+, the average amount of time for commercials is four minutes per hour. On Hulu, it’s just over six minutes.

“There was always this notion that people don’t like ads,” said Rita Ferro, the president of ad sales at Disney. “I don’t think that’s true. People don’t like bad advertising or a bad advertising experience.”

In the data-rich streaming world, she argued, the advertising experience is better informed than it was on traditional television, and the company knows what a person’s viewing preferences are and “what products are relevant to you,” she said.

Mr. Wieser, the analyst and founder of the consulting firm Madison and Wall, said he expected that even with ads running on streaming services, overall ad revenue would continue to decline for media companies. He projects that the amount of time spent watching ads on television — both streaming and traditional network and cable TV — will fall by 24 percent by 2027 compared with last year.

Part of the reason, he said, is that many people will continue to pay extra to avoid ads on services like Netflix. “The vast majority of Netflix subscribers will never choose an ad-supported option of any price,” he said.

Still, viewers may have no choice in some cases. Even Netflix subscribers who pay more than $15 a month for the ad-free tier will be exposed to commercials if they tune into the streamer’s pair of N.F.L. Christmas games this year, or W.W.E. shows next year. The same goes for subscribers of Peacock, Paramount+ and Prime Video, which also carry live sports.

“Amazon is selling the N.F.L. How is that different from what Fox is selling or what CBS is selling?” said Joe Marchese, a former head of ad sales for the Fox networks group who is now a venture capitalist. “Netflix is pitching a Shonda Rhimes show. The thing you’re pitching to advertisers — here’s culture creation, would you like to be adjacent to it? That sounds exactly the same. The only difference is who’s doing it.”

And in some cases, a half-century’s worth of precedent is shattering.

For decades, HBO offered zero commercials. But now, advertisers can run commercials on Max’s ad tier during episodes of older HBO fare, and an ad before a new HBO series. At the company’s upfront presentation for advertisers, executives played a clip from a GMC Sierra pickup truck commercial that ran on Max’s ad tier before episodes of HBO’s “True Detective.”

It was especially striking to see Casey Bloys, the chairman of HBO and a two-decade veteran of the network who is more accustomed to script development than pitching marketers, promoting programming “that reaches multiple audiences” during the upfront. While reeling off stats about the audience makeup of HBO’s documentary series “Hard Knocks,” Mr. Bloys stumbled on his words, chuckled and said, “I’m new to the advertising banter.”

At Disney’s upfront event, the ABC late-night host Jimmy Kimmel mocked media companies suddenly reconnecting with their roots, including by bundling different streaming services into one package. Viewers “can turn on their TV and get all the channels in one package for one price, all supported by ads,” he said. “We call it basic cable, and it’s going to blow your minds.”

And then Mr. Kimmel took aim at Netflix, reminding marketers that they “spent years ignoring you, sneering at you.”

“Remember when Netflix thought they were above all this?” he said. “They came in, they destroyed commercial television. And now, guess what they want to sell you. Commercials. On television.”

Be the first to comment