Getty

GettyThe £8m Longitude Prize has been won after a decade-long competition to find new tools to tackle the scourge of superbugs.

It has been awarded for a test that rapidly detects whether an infection is caused by bacteria and identifies the right antibiotics to treat it.

The test takes 45 minutes, compared with three days using traditional methods.

The original work was done by Swedish researchers and the test is now being sold by the company Sysmex Astrego.

Silent pandemic

The Longitude Prize – with a financial reward nearly 10 times that of a Nobel – was inspired by a contest in 1714.

It was won by John Harrison, who developed a precise clock allowing sailors to pinpoint their position at sea – one of the greatest challenges of the 18th Century.

Fast forward 300 years – and the modern blight of superbugs was the focus.

Infections that resist the drugs used to treat them are estimated to kill more than a million people every year. It is known as the silent pandemic.

“Without antibiotics, modern medicine as we know it is in real danger of collapse,” UK special envoy on antimicrobial resistance Dame Sally Davies says.

Every time an antibiotic is used creates an opportunity for bacteria in the body to evolve resistance to it.

Resistance gives those bacteria a survival advantage and they spread, which is why the life-saving drugs should be used only when it is certain they will work.

Sysmex Astrego

Sysmex AstregoThe test works in urinary tract infections, which affect most women at some point and account for a fifth of antibiotics prescribed in England.

When the patient first arrives in hospital, or at a doctor’s surgery, it is not easy to tell if their infection is caused by bacteria, viruses or even fungi.

Doctors can send a sample to a clinical microbiology laboratory – but this means growing the bacteria on a petri dish and can take three days to reveal the cause and which antibiotics the infection may be susceptible to.

In the meantime, antibiotic treatment is often started anyway because of the risk of symptoms becoming much worse or even causing sepsis.

Tiny doses

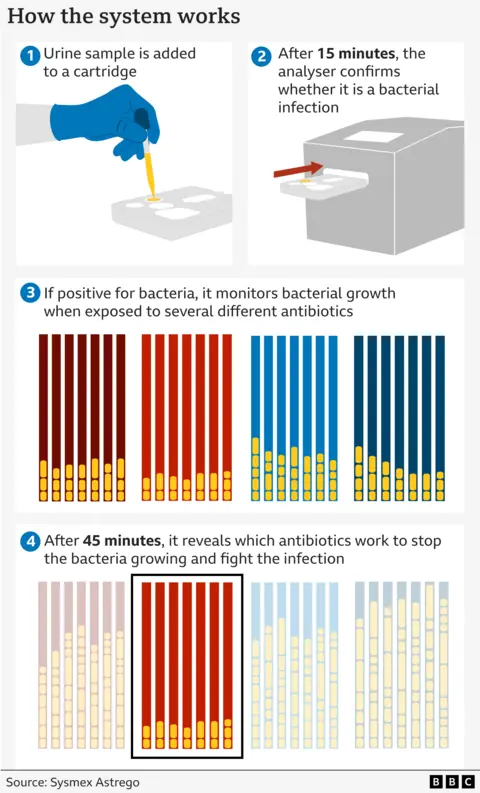

The prize-winning test, however, reveals within 15 minutes whether the infection is bacterial – and within 45 minutes, which antibiotics work.

It starts with a urine sample, which is squirted into a cartridge containing tiny doses of five different antibiotics and placed inside a machine.

Any bacteria are forced – in single file – into one of thousands of channels inside the cartridge.

The machine then uses microscopy to monitor how any bacteria grow in the presence of the different drugs.

And the antibiotics that lead to little or no growth are the most likely to work.

A panel of 17 experts chose the winner from more than 250 entries.

Prof Johan Elf, from Uppsala University, said they had been working on measurement technology when the prize had been announced, a decade ago.

They then realised their work “could be really useful in the fight against antimicrobial resistance” and began working on the test.

Sysmex Astrego said it was rolling out the test in Europe and running studies in the UK.

“The £8m prize will support us to tailor the test for use with different kinds of UTIs and antibiotics, speeding up access for more patients,” one of the company’s founders, Mikael Olsson, said.

‘Rich countries’

Dame Sally said the winner “lays the groundwork for a sea-change in how we manage these precious medicines” and rapid tests would mean patients received the “right drug, first time”.

The technology is not currently recommended for use in the NHS, however.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence is still monitoring the difference it makes to patients and its cost-effectiveness.

Meanwhile, Prof Laura Piddock, from the Global Antibiotic Research and Development Partnership, said it would be a ”game-changer” only in rich countries that could afford it, while antimicrobial resistance was a global problem that was “worse” than when the prize had been announced.

Getty

GettyIn 1714, the UK government’s Longitude Act offered £20,000 to whoever could solve the challenge of working out how far east or west ships at sea were.

This required knowing the time on board as well as back at home – each four-minute time difference means one degree of longitude.

The ship’s time could be set using the height of the Sun each day – but the ocean waves and the humidity would disrupt the delicate mechanisms in the clock trying to keep time back in port.

Harrison, a self-taught clockmaker from Yorkshire, solved the problem but then battled the establishment for years to be deemed the winner.

The latest Longitude Prize was run by Challenge Works, a part of the innovation agency Nesta.

“When there is a challenge of gargantuan proportions in desperate need of real-world solutions, prizes attract the brightest minds to solve the problem,” Challenge Works managing director Tris Dyson said.

Another Longitude Prize, worth £4.4m, has now been announced – to help people in the earliest stages of dementia live independently.

Follow James on X, formerly known as Twitter.

Be the first to comment