This is Part 2 of GMA News Online’s series highlighting LGBTQIA+ issues in the police force and military.

Read Part 1 here: What it’s like to be in the police force and be LGBTQIA+

For the military, ancient Greece history recorded the Sacred Band of Thebes, a military unit from 378 BCE which consisted of male lovers who were known for their battle skills. Same-sex relationships were also recorded among the Samurai class in Japan. Throughout history, homosexual behavior has been considered a criminal offense by civilian and military law in some countries. Trials and executions were done against members of the Knights Templar in the 14th century and British sailors during the Napoleonic Wars over homosexuality.

Official bans on gays in the military were first reported in the early 20th century. The United States launched a ban in a revision of the Articles of War of 1916 and the UK first prohibited homosexuality in the Army and Air Force Acts in 1955. Some nations like Sweden never introduced bans on homosexuality in the military but issued recommendations on exempting homosexuals from military service.

The Philippine government officially ended the gay ban in the military around 2010. In 2012, the Philippine Military Academy welcomed openly gay and lesbian applicants, giving them the chance to serve in the military.

Followed kuya’s footsteps in the military

Unlike Police Lieutenant Jessie G. Quitevis, a soldier in Nueva Ecija had to suppress her identity and expression as a transgender woman entering the Philippine Army.

Moirah or Private Ramon Mangaoang of the 7th Infantry Division said she joined the Philippine Army because it was a dream of her family for her and it was the dominant career where she grew up. She was raised in a family of soldiers. Her brother, who was an Army fighter, died in an encounter in the Davao Region in 2016. Moirah was made aware of a tradition that when a soldier died on duty, one of their siblings should join the Army as a replacement. During that time, her brother was the only person of legal age among the siblings. At first, she turned down the offer of her brother’s colleagues.

“Last 2016 po, ‘yung pinakapanganay po naming kuya is namatay po siya sa isang giyera doon po sa may bandang Davao Region. Noong namatay po siya, may mga pumunta po sa burol ng kuya ko na nag-uudyok po sa akin na pumasok nga sa military dahil tradisyon na kasi ‘yun e sa Army na kapag may namatay na isa sa magkakapatid na sundalo, ang papalit isa rin sa mga kapatid. That time, ako lang po ‘yung qualified na pumasok sa military because of my age,” she said.

(Last 2016, our eldest brother died in a firefight in the Davao Region. During his wake, some soldiers went and encouraged me to enter the military because they said there is a tradition wherein if a soldier dies, one of his siblings should be a soldier too. That time, I was the only one qualified to enter the military because of my age.)

“Pero I refused din kasi parang sa gender identity ko, kasi that time cross-dresser na ako e. So ‘yun, sabi ko parang hindi ko gusto na pumasok. At saka hindi ko rin talaga siya nilo-look up noong bata ako na magiging sundalo ako kasi nga bakla po talaga ako,” she added.

(But I refused due to my gender identity. I was a cross-dresser that time. I also did not dream of becoming a soldier when I was a child because I was gay.)

Mangaoang and kuya who joined the Army. Photo was taken in 2009.

Mangaoang was in college and taking a degree in secondary education. However, she decided to go to Metro Manila at age 18 to find a job. She had a difficult time getting a job though due to her lack of experience. On the last day of her attempt to find a job, Mangaoang saw some military personnel walking on the street. They reminded her of her deceased brother. And so she decided to join the Philippine Army.

“Why not give it a try? Baka doon ako lilinya. Titignan ko lang din. It’s now or never. Siyempre, meron ding age limit ang pag-a-Army e, hanggang 26 years old lang. Binigyan ko rin ng shot ‘yung offer sa akin ng mga kasamahan ng kuya ko,” she said.

(Maybe that’s where I am really meant for. I’ll see. It’s now or never. There was also an age limit in joining the Army. Applicants had to be 26 years old or younger. I gave it a shot – the offer made by my brother’s fellow soldiers to join the military.)

Right away, Mangaoang said she cut her long hair in preparation for her application. As a transgender woman, she said it was a wild decision for her.

“Crazy thought siya e. Cross-dresser ako. Ang haba-haba ng hair ko that time tapos mag-a-apply ka sa Army. Sa sobrang kabaliwan ko that time, pinutol ko agad ‘yung hair ko on that moment na sinabi ko na gustong bigyan ng chance ang sarili ko sa Army. So ang ginawa ko, okay, decided na ako. Talagang pinutol ko ‘yung hair ko. Kinabukasan nagulat ‘yung tinutuluyan ko sa Manila. ‘Bakit ka naggupit ng buhok mo? Nababaliw ka na?’ ‘Hindi naman po,’ kako. ‘Kasi parang gusto ko na rin pong sumunod sa kuya ko.’ Pumunta ako sa barber shop. Nagpagupit na ako noon. Panlalaki talaga na hair,” she said.

(It was a crazy thought. I was a cross-dresser. My hair was so long that time then I would apply to join the Army. In my craziness that time, I had my hair cut right at that moment. The next day, my housemates in Manila were shocked. ‘Why did you cut your hair? Are you crazy?’ ‘Not really, I said. I think I want to follow in my brother’s footsteps.’ I went to a barber shop for the male-style haircut.)

Her new masculine look also shocked her family when she returned to Nueva Ecija from Metro Manila. According to Manaoang, her father was happy that she would join the military. But not her mother. Manaoang said her mother feared that she will end up as another casualty in their family of soldiers like what happened to her brother. She said their family was traumatized by her brother’s passing.

“Yung family ko ang iniisip nila pumunta ako sa Manila para humanap ng trabaho. Pag-uwi ko galing ng Manila, umuwi ko sa probinsya dito sa Nueva Ecija. Nagulat ‘yung tatay ko, nagwawalis siya sa labas ng bahay. Umaga ‘yun e. Hindi niya ako namumukhaan hanggang sa makita niya. ‘Hoy, bakit ka nagpagupit ng buhok? Ano bang naisip mo?’ Sinabi ko nga na gusto ko nang sundan si kuya. Natuwa naman si papa. Pero ‘yung nanay ko, medyo hindi siya natuwa kasi siyempre na-trauma siya sa nangyari sa kuya ko. Hanggang sa natanggap na lang din siya na susunod ako sa kuya ko,” she added.

(My family thought I went to Manila to find a job. When I came back to Nueva Ecija from Manila, my father, who was sweeping the yard that morning, did not recognize me. ‘Hey, why did you cut your hair? What are you thinking?’ I said I want to follow in kuya’s footsteps. He was happy. But my mother was not so glad about it because she had trauma after what happened to my brother. Eventually she accepted that I would follow my brother’s footsteps and join the Army.)

Infantry

Mangaoang was deployed to the same area and role as her brother. She conducted patrols and operations as well as civil relation works.

“After kong mag-training sa Army, na-deploy po ako sa Infantry Battalion. So knowing Infantry Battalion, ganu’n din kasi si kuya. Ganu’n din ‘yung work niya, nagpapatrol, nag-o-operate, mga civil relations work. Ganu’n din po ‘yung ginagawa ko. Tumutulong po ako sa mga civilians. For example, kapag may mga bagyo, natural disasters. Nagre-rescue, nagbibigay ng relief operations. Nagpapatrol din ako, nag-o-operate po sa mga kabundukan,” she added.

(After my Army training, I was deployed to the Infantry Battalion. That was also where my kuya was assigned before. So we did the same things like patrolling, operating, doing civil relations work. I would help civilians out for example when there are typhoons, natural disasters. We would join rescue and relief operations. I would also join patrols and operations in mountains.)

Mangaoang said she will never forget the dangerous moments that she experienced while in the service. There were times when their teams heard gunshots during their patrols in mountainous areas. She said these experiences triggered her trauma considering that her brother died in situations like these.

“Ang pinaka hindi ko malilimutan siguro ‘yung mga times na naglalakad kami, nag-o-operate kami, ‘yung mga delikado moments. Siguro ‘yung mga nasa kabundukan kami nagpapatrol. There was this one time na nakakaloka. Nag-o-operate kami and first time ko ‘yun na ma-experience na biglang may pumutok. Kasi nakalinya kami. ‘Yung nasa unahan ng linya namin habang nagpa-patrol kami bigla siyang pumutok. So akala ko talaga may kalaban na. So nag-drop kaming lahat, nag-drop din ako,” she said.

(I could not forget the times when we would walk, conduct sensitive patrols in the mountains. There was one time that was nerve-wracking. We were operating and it was my first time to hear a gunshot. We were in line. The one in front then fired a shot. So I really thought the enemies were there. We all dropped to the ground.)

“Akala ko ‘yun na, katapusan na ng buhay kasi siyempre na-trauma din ako sa kuya ko e kasi doon din siya exactly namatay sa ganu’ng operation. Sabi ko, ito na siguro ‘yung last moment ko sa Earth. Baka dito na ako mamamatay. Pero siyempre bilang isang sundalo, after ng training, talagang nag-sink in na sa utak ko na dito na talaga ako mamamatay,” she added.

(I thought that was the end of my life because I was also traumatized with what happened to my brother. He died in such an operation. I told myself, maybe this is my last moment on Earth. Maybe this is where I will die. But of course as a soldier, after training, you think that you will die in the battlefield.

Mangaoang said she also faced discrimination even in high school. She said a Physical Education teacher once failed her even though she was really performing well in the subject. She was also shamed for requesting the school director to allow her to take the Technology and Livelihood Education subject (TLE) under the program for girls instead of for boys.

This is why some of her high school classmates who also pursued a military career were surprised when they saw her training for the Army. According to Mangaoang, many of her classmates spread the information about her sexual identity. But many of her co-trainees supported her.

Training for the Army

“At first parang shookt sila noong nakita nila ako. Kasi ‘yung iba kasi doon sa mga ka-batch ko na naging kaklase ko sa Army is mga kakilala ko na before, mga tagarito rin, anak ng miskit. So nagulat sila. Pero ‘yung ibang mga kaklase ko, hindi talaga ako kakilala. So chika-chika nila na, ‘Bakla yan.’ Hanggang sa nag-iiba ‘yung pakikitungo nila sa akin. Kunwari, kapag turn ko na mag-push up, kinakantsawan nila ‘ko, ‘Whoo, kaya mo yan.’ Hindi naman kinakantyawan na in a negative way; parang in a positive way. Talagang ina-uplift din talaga nila ako. Feeling ko proud sila sa akin na may isang gay na nag-stood up just to prove na to break the barrier, stereotype na para lang sa masculine o panglalaki ‘yung Army,” she said.

(At first they were shocked when they saw me. Some of those in my batch in the Army knew me from before. We lived in the same area. So they were surprised. My other classmates, however, really did not know me. So those who knew me would tell others that I was gay. Some of them changed their attitude toward me. For instance, when it was my turn to do push-ups, they would heckle me and say, ‘Whoo, you can do it.’ The heckling was not in a negative way though.)

Mangaoang also received homophobic remarks from her superiors whenever she failed to do a task.

“Merong isang senior parang kinukuwestiyon niya ‘yung pagkatao ko dahil lang sa hindi ako makapagsibak ng kahoy. Doon kasi sa ano namin sa napag-deployan sa atin is sobrang hirap talaga ng pamumuhay. Talagang buhay sundalo siya. Hindi siya ‘yung makikita mo ‘di ba, kapag nakakita ka ng beking sundalo parang iisipin mo, ‘Ay sa ano lang ‘yan, sa office lang ‘yan, nagta-type.’ Hindi! Actually ako rin, ganu’n din ‘yung inisip ko, in-envision ko sa sarili ko. Siguro mag-aano lang ako, ko-computer-computer, office works, puro paperworks. Pero hindi ‘yun ‘yung nangyari,” she said.

(There was a senior who seemed to challenge my character just because I could not chop firewood. The area where we were deployed was really in a remote area and life was hard there. It was a challenge for soldiers. You would think being LGBT in the military would entail just being in an office, typing on computers, doing office works, attending to paperworks. But that was not what happened.)

“Ang ginagawa nila sa akin noon, pinagsisibak ako ng kahoy, pinagtrotroso ako sa kakahuyan. Talagang hindi ko siya usually ginagawa. Kaya sabi ko doon sa senior ko, ‘Hindi ko po talaga kaya pero ita-try ko po’. Alam mo ba kung anong sinabi sa akin? ‘Bakla ka kasi!’ Alam mo ‘yung mga salitang masasakit. ‘Bakit ka pa nagsundalo e bakla ka naman. Wala kang kuwenta!’ Actually, umiyak talaga ako in that very moment. Talagang sobrang gumuho ‘yung mundo ko. At the same time, sinabi ko, ‘Oo nga ‘no, bakit nga ba nag-sundalo ako?’ Pero siyempre, tinry ko na hindi kami ganu’ng mga bakla. So tinry ko pa rin talagang matutong magsibak ng kahoy. Until now, nagsisibak ako ng kahoy,” she added.

(What they did to me was they made me chop firewood, get lumber from the forest. It was not something I would really do. So I told my senior, ‘I cannot really do it but I will try.’ You know what he said? ‘It’s because you’re gay! You are good for nothing!’ The words stung. Actually, I cried at that very moment. My world crumbled. At the same time, I said, ‘Why did I ever become a soldier?’ But of course I tried to learn how to chop firewood. Until now, I chop firewood.)

In the frontlines helping civilians

For Mangaoang, among her greatest achievements in the military service were rescuing people during natural disasters and making her colleagues laugh whenever they had low morale.

“Ang greatest achievement ko siguro sa pagsusundalo, kapag may nangangailangan ng tulong mo, ikaw ‘yung may kakayanang tumulong sa mga civilians. Lalo na kapag may mga natural disasters, lindol, bagyo, kami talaga ‘yung nasa frontline. Kapag nakikita ko ‘yung mga pamilya na nakalubog ‘yung bahay nila sa baha tapos paparating kami naka-speedboat kami, natutuwa sila na paparating kami, ang sarap sa feeling. Para kang superhero na dumadating sa isang pamayanan na ikaw ang tutulong. Para sa akin ‘yun ‘yung greatest achievement ko,” she said.

(My greatest achievement I guess in being a soldier is helping civilians who need help. Especially when there are natural disasters like earthquakes, typhoons, we are the ones on the frontline. When we arrive on a speedboat to rescue a family whose house is already flooded, they are so glad to see us. It’s a great feeling. You’re like a superhero who arrives in the community to help. For me that is my greatest achievement.)

“Also kung ambag man, siguro ang naiambag ko bilang isang transgender o gay sa Philippine Army ay ‘yung source of happiness nila kapag nalo-low morale sila. Nalulungkot sila. Kasi ako naman is very jolly person ako, though, nalulungkot din naman ako kapag nasa field ako. Siyempre, malayo sa family. Ang tanging magagawa ko na lang siguro doon is mapasaya sila. Knowing us, kami sa LGBT community, kami talaga ay mga jolly persons. Ang naging ambag sa Philippine Army sa kasamahan ko is mabigyan sila ng kahit papaano ng ngiti, kaunting ngiti sa kanilang mga labi,” she added.

(Also, as a transgender or gay in the Philippine Army, I was able to be a source of happiness to the troops whenever they have low morale. They get sad. I’m a very jolly person but I also get sad when I’m out on the field as I’m away from my family. What I can do is make them happy. Knowing us, the LGBT community, we really are jolly persons. My contribution to the Philippine Army is being able to make the soldiers smile somehow.)

With fellow soldiers

After around three years of pursuing a military career, Mangaoang left the service. She felt it was time for her to fulfill her own dream after pursuing her family’s dream to have her join the military.

“Ang naging goal ko lang naman kasi kaya kaya ako nagsundalo, gusto ko ring i-prove sa tatay ko, which is sundalo rin, na kahit ganito ako is kayang-kaya ko rin namang gawin ‘yung kayang gawin ng kuya ko at niya. Dito sa family namin puro kami sundalo e. ‘Yung tita, pinsan, tito. Lahat mga sundalo. Gusto ko sigurong ipamukha sa kanila na kahit ganito ako, kaya ko rin,” she said.

(My goal in becoming a soldier is to prove to my father, who was also a soldier, that even if I am like this, I can also do what he and my brother were able to do. We are a family of soldiers. My aunt, cousin, uncle, all of them were soldiers. I guess I wanted to show them that even if I am like this, I can do it.)

“Kaya ako umalis sa service naman is gusto ko rin naman matupad naman ‘yung pangarap ko para sa sarili ko. Natapos na ‘yun e. Natupad ko na ‘yung pangarap para sa akin. This time gusto ko namang tuparin ‘yung pangarap ko para sa sarili ko,” she added.

(I left the service to pursue my own dream. I was already done with fulfilling their dream for me. This time I want to do what I want to do.)

Pursuing her dream.

Now, Mangaoang continues to pursue her passion for teaching, make-up, and pageantry despite initially struggling to earn a stable income since the salary in the military is higher compared to that in other industries.

“I am planning to take the Licensure Examination for Teachers. Hopefully, sana po makapasa. After ko pong umalis sa service, sobra po akong nahirapan ‘yung income. Siyempre alam naman po natin na doblado ang suweldo ng sundalo, ‘di ba. Talagang nanghihinayang rin po ako tuwing may bonus. May mga incentives na paparating,” she said.

(I am planning to take the Licensure Examination for Teachers. Hopefully, I will pass it. After I left the service, I had a hard time earning. Or course we know that soldiers earn more, right? I missed the bonuses and incentives.)

“Sobra po akong nanghihinayang pero nagiging masaya na rin ako on the part na nagagawa ko ‘yung gusto ko. ‘Yung walang kumikuwestyon sa ginagawa ko. Ngayon, make-up artist na ako. Ang dami ko nang source of income. Mas malaki pa ‘yung monthly income ko kaysa nu’ng sundalo pa ako. Bonus pa nagagawa ko ‘yung gusto kong gawin. Mahaba pa ‘yung buhok ko ngayon unlike before,” she added.

(I missed those but I became happy because I was doing what I wanted to do. No one was questioning what I was doing. Now I am a make-up artist. I have many sources of income. My monthly income now is higher than what I earned when I was a soldier. The bonus is that I like what I do. My hair is longer now, unlike before.)

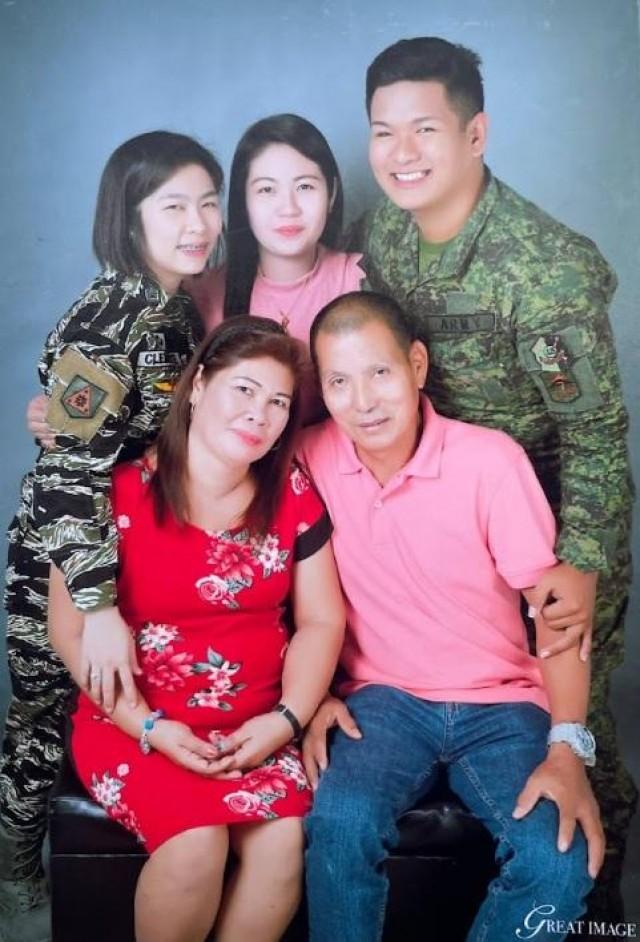

Mangaoang and family

No discrimination in the AFP

Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) spokesperson Colonel Francel Padilla said the military organization has no recruitment policy that discriminates against the LGBTQ community. However, Padilla said they only recognize “two genders.” While in the uniformed service, Padilla said military personnel who are LGBTQ members should keep the dignity of the uniform, discipline, propriety, and decorum, as well as meet the standards of the service.

“Walang policy ‘yung AFP regarding sa LGBTQ. If you look at the pinaka-eligibility requirements, must be male and female, able-bodied, should pass the medical and physical exams. Of course, male and female, doon pa rin sila maa-affiliate. So wala talagang more than those two genders,” she said.

(The AFP has no policy regarding LGBTQ. If you look at the eligibility requirements, they must be male and female, able-bodied, should pass the medical and physical exams. Of course, they still have to be affiliated with either male or female. There is really nothing beyond those two genders.)

“But, inside siyempre, hindi natin mapagkakaila, meron pa rin tayong mga kasamahan na ganu’n ‘yung affiliations but we accept them as they are as long as they accept na ‘yun talaga ‘yung pinasok nilang serbisyo. They are in the uniformed service. And they should maintain the dignity of the uniform, observing discipline, propriety, at saka decorum, and of course measure up to these standards of the service,” she added.

(But inside [the service], of course, we cannot deny that we have personnel with such [LGBT] affiliations. We accept them as they are as long as they accept that this is the service they entered.)

Padilla said that culturally the AFP is not yet very open to the public display of affection like kissing among LGBT members. She noted that even for heterosexual individuals, the AFP also discourages public display of affection except for special occasions. According to her, only holdings hands and cheek to cheek kisses are accepted for now.

“Part pa rin kasi ‘yun ng discipline na sinasabi natin. When you are in uniform, it is shunned ‘yung public display of affection. Unless, siyempre there are certain instances, siyempre graduation, darating ‘yung pamilya mo, yayakapin ka. Those are acceptable public display of affection. But for relationships, siyempre culturally lang din naman, hindi naman talaga sa serbisyo siya, but culturally hindi pa rin tayo very open like kissing in public and all that. Medyo doon pa rin tayo sa holding hands, beso-beso. Makikita naman natin e kapag meron talagang iba. So nasa judgment call na rin ng mga nakakakita if they will be reported as such,” she said.

(It is still part of the discipline. When you are in uniform, public display of affection is shunned. Unless in certain instances such as graduation and members of your family arrive and embrace you. Those are acceptable public displays of affection. But for relationships, of course, culturally and not just in the service, we are not yet very open to acts such as kissing in public and all that. We are still at the level of holding hands and doing air kisses. We notice if there is something different. So it is the judgment call of those who witness something if they will report any such incident.)

Padilla said the AFP strictly follows its parameters when it comes to promotions and sexual identity is not being considered.

“The Armed Forces of the Philippines, as long as you’re performing, meron po kasi tayong parameters for our promotion. May time-in grade. Meron kasi tayong tinatawag na quantitative rating sheet, ‘yung QRS na tinatawag natin gives you points to be promoted. So kailangan dumaan ka sa certain positions. Umikot ka sa geographical assignments. You earn points by that. And regardless of your affiliations in terms of gender, hindi siya nagma-matter. Kung ano po ‘yung QRS points mo, that is how you would be considered for promotion,” she said.

(In the Armed Forces of the Philippines, as long as you’re performing… there are parameters for our promotion. There’s time-in grade. There’s a quantitative rating sheet or QRS which records points for promotion. You need to go through certain positions, take geographical assignments. You earn points by that. Your affiliations in terms of gender do not matter. You will be considered for promotion based on your QRS points.)

When it comes to protection of LGBT personnel, Padilla said the AFP’s gender and development initiatives are only guided by the existing laws in connection with the LGBT community. According to her, the AFP has established gender and development offices (GAD) from higher to lower offices of the military organization to address the concern of LGBT personnel.

“But we have to look at the bigger perspective na ang AFP po based our gender and development [policy] doon din sa batas ng Pilipinas, so parang IRR of sorts ang GAD ng Armed Forces of the Philippines down to the different branches of service ng ating Air Force, Army at Navy. So kung ano ang batas, sumusunod lang tayo doon pababa hanggang sa lowest,” she said.

(But we have to look at the bigger perspective that the AFP based its gender and development [GAD policy] on Philippine law. The GAD of the AFP is like the IRR [implementing rules and regulations] of sorts for the different branches of service like Air Force, Army, and Navy. We just follow the law.)

“Ang mga milestones natin diyan is nagkaroon tayo nga ng GAD offices all over the AFP. So from the AFP sa pinakataas, meron tayo, and then meron tayo sa mga branches of service down to the lowest units. Tinapatan din natin ‘yung mga violence desks ng pulis, ‘yung mga GBV desks, gender-based violence desks, meron tayo niyan. So hindi po tayo nag-didiscriminate ng any gender. Kahit anong gender mo – lalaki, babae, LGBTQ+ – you are open to approach any member of the GAD,” she added.

(The milestones there is that we had GAD offices all over the AFP, from the highest, the AFP, down to the lowest units in the branches of service. We have our own counterparts of the police’s violence desks. We have GBV or gender-based violence desks. We do not discriminate based on gender. Whatever your gender is – male, female, LGBTQ+ – you are open to approach any member of the GAD.)

Padilla said the military organization remains open to improving their programs and policies for the LGBT community. She said the AFP is a learning organization.

“Sa Armed Forces of the Philippines, we are open for any dialogue that will further broaden our perspective in the plight of the LGBTQ+ na community as well as forward our intention non-discrimination in the military service. Nakita kasi natin (We saw that it’s) to each his own ‘yan e. We have our own talents. We have our own skills to offer in the table. Itong LGBTQ community they have a lot to offer. They are very artistic. They have the tendency to think outside the box. These are all very welcome naman even in the military service,” she said.

“The AFP is a learning organization and we are adapting to the times. Ito na ‘yung modern day pull of personnel natin and of course we do not discriminate,” she added.

Around the world

According to the latest report of equality monitoring group Equaldex in 2024, the following are the policies of different countries on allowing LGBT persons to serve in the military:

LEGAL (60 countries)

Asia:

- Bhutan

- Israel

- Japan

- Kazakhstan

- Nepal

- Philippines

- Singapore

- Thailand

- Vietnam

Europe:

- Austria

- Belgium

- Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Croatia

- Cyprus

- Czech Republic

- Denmark

- Estonia

- Finland

- France

- Germany

- Greece

- Hungary

- Ireland

- Luxembourg

- Malta

- Montenegro

- Netherlands

- Norway

- Serbia

- Slovakia

- Slovenia

- Spain

- Sweden

- Ukraine

- United Kingdom

North America:

- Antigua and Barbuda

- Bahamas

- Barbados

- Canada

- Cuba

- Jamaica

- Saint Kitts and Nevis

- Trinidad and Tobago

- United States

Africa:

Oceania:

- Australia

- Fiji

- New Zealand

- Papua New Guinea

- Tonga

South America:

- Argentina

- Bolivia

- Brazil

- Chile

- Colombia

- Ecuador

- Guyana

- Paraguay

- Suriname

- Uruguay

LESBIANS, GAYS, BISEXUALS PERMITTED BUT TRANSGENDERS BANNED (40 countries)

Asia:

Europe:

- Albania

- Bulgaria

- Georgia

- Italy

- Kosovo

- Latvia

- Lithuania

- Moldova

- North Macedonia

- Poland

- Portugal

- Romania

- Russia

- San Marino

- Switzerland

- Vatican City

- North America

- El Salvador

- Guatemala

- Honduras

- Mexico

Africa:

- Angola

- Benin

- Botswana

- Burkina Faso

- Equatorial Guinea

- Gabon

- Guinea-Bissau

- Lesotho

- Madagascar

- Mozambique

- Republic of the Congo

- Rwanda

- Sao Tome and Principe

- Seychelles

- Zimbabwe

South America

DON’T ASK, DON’T TELL (14 countries)

Asia:

- Jordan

- Kuwait

- Kyrgyzstan

- Lebanon

- Maldives

- North Korea

- Syria

- Tajikistan

Europe:

- Armenia

- Azerbaijan

- Belarus

Africa:

- Côte d’Ivoire

- Liberia

- Zambia

ILLEGAL (46 countries)

Asia:

- Afghanistan

- Bangladesh

- Brunei

- India

- Indonesia

- Iran

- Iraq

- Malaysia

- Myanmar

- Pakistan

- Qatar

- Saudi Arabia

- South Korea

- Sri Lanka

- United Arab Emirates

- Uzbekistan

- Yemen

Europe:

North America:

- Dominican Republic

- Nicaragua

Africa:

- Algeria

- Burundi

- Cameroon

- Chad

- Comoros

- Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Egypt

- Eritrea

- Ethiopia

- Gambia

- Ghana

- Guinea

- Kenya

- Libya

- Malawi

- Mauritania

- Morocco

- Nigeria

- Senegal

- Sierra Leone

- Somalia

- South Sudan

- Sudan

- Tanzania

- Togo

- Uganda

NO DATA, NO LAWS, N/A, OR AMBIGUOUS (37 countries)

Asia:

- Bahrain

- China

- Laos

- Oman

- Palestine

- Timor-Leste

- Turkmenistan

Europe:

- Andorra

- Iceland

- Liechtenstein

- Monaco

North America:

- Belize

- Costa Rica

- Dominica

- Grenada

- Haiti

- Panama

- Saint Lucia

- Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

Africa:

- Cape Verde

- Central African Republic

- Djibouti

- Eswatini

- Mauritius

- Namibia

- Niger

- Tunisia

Oceania:

- Federated States of Micronesia

- Kiribati

- Marshall Islands

- Nauru

- Palau

- Samoa

- Solomon Islands

- Tuvalu

- Vanuatu

Antarctica:

The Hague report

Based on The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies report on LGBT military personnel in 2014, there was no scientific evidence that homosexual, bisexual, and transgender persons are less capable of providing the skills and attributes that militaries demand. In fact, many countries seek LGBT people for their recruitment strategy as they believe that the community may have skills they need for the organization.

“Evidence shows that acknowledging LGBT service has no necessary negative effects on any of these components. Furthermore, armed forces which take a positive approach to LGBT participation and which practice effective management may benefit from a more focused, trusting, professional, and respectful workforce,” the report said.

The Hague report said the known presence of colleagues with different sexual orientations or gender identities does not affect the work ethics of military personnel. The morale of military members may be determined by the support they receive, the quality of leadership, the belief that they are making an important contribution, and an affinity with the organization’s goals.

“Recent changing attitudes toward LGBT people suggest that it is becoming rarer for people to feel disconcerted by the presence of acknowledged LGBT colleagues. A wealth of anecdotal evidence additionally suggests that heterosexual personnel serving alongside LGBT people frequently develop increasingly positive attitudes toward their colleagues over time,” the report said.

“Even if some service members feel uncomfortable serving with known LGBT individuals, such attitudes have been found unlikely to manifest themselves in performance decreases. Requiring service members to perform at their best alongside other personnel of all different backgrounds is commonplace in armed forces, particularly in the context of international cooperation,” it added.

According to the report, LGBT soldiers’ coming out can benefit the morale of many individuals including those who are not even part of the community. These LGBT personnel may experience better mental health, feel less vulnerable to blackmail, and feel better at ease when they do not hide part of their identity.

“There is also evidence to suggest that attempting to downplay or hide one’s identity or affiliation can be a costly distraction, and can undermine collegial relations when reticence and secrecy create suspicion or distrust. For a military unit, coming out puts an end to intrigue and speculation about sexual orientation and ‘allows [personnel] to focus on their jobs,’” the report said.

“If armed forces want to benefit from the increased morale and minimize the negative effects associated with LGBT personnel, they may consider the factors which increase the likelihood of LGBT people to come out. These factors include the perception of a supportive environment and the belief that one’s colleagues will behave in a respectful manner,” it added.

In militaries that have repealed exclusionary policies, The Hague report states that the likelihood of a significant change in recruitment and retention numbers is low. The exclusion of LGBT members from the military service is costly, the report said.

“Senior officers had to spend time and resources investigating allegations of homosexuality; and personnel that had received costly training, equipment, and transportation were discharged because their sexual orientation became known. Evidence moreover indicates that LGBT personnel leave organizations that pursue an exclusionary policy and prefer organizations that have an inclusive approach. Since the replacement of personnel is expensive, the armed forces may benefit from an environment which favors the retention of LGBT personnel,” the report said.

The Hague report said that harassment against LGBT members in the military can be addressed without excluding them from the service. According to the report, a strict universal code of conduct can be imposed that requires respectful behavior among all service members and enforces a zero-tolerance policy towards any kind of discrimination. Militaries benefit from enforcing such a policy enhancing good order and discipline among the ranks. Strict policies are particularly beneficial for multinational cooperation, where soldiers need to be able to work with colleagues of different social and cultural backgrounds, the report said.

“Secrets about sexual orientation and gender identity have enabled blackmail to take place in armed forces. If the armed forces work to ensure an environment in which LGBT service members do not face negative consequences for revealing their sexual orientation or gender identity, then the risk of blackmail is diminished. Operating a policy which allows service members to come out, and which works to reduce the negative consequences associated with coming out, therefore not only benefits LGBT service members, but also benefits armed forces by reducing the vulnerability of personnel to blackmail,” the report said.

LGBT Military Index

In The Hague’s LGBT Military Index in 2014, countries were classified into five categories based on their policies regarding the LGBT community with “Inclusion” as the highest level and “Persecution” the lowest.

Under “Inclusion” level, these countries showed multiple active, concerted efforts to improve LGBT inclusion in the armed force:

- New Zealand

- The Netherlands

- The United Kingdom

- Sweden

- Australia

- Canada

- Denmark

- Belgium

- Israel

- France

- Spain

According to The Hague report, these countries “highlight opportunities for militaries interested in inclusion to share experiences and best practices. LGBT inclusion also correlates with human development and democracy indicators. For policymakers and advocates of LGBT military inclusion, this suggests that LGBT inclusion generally happens as part of a wider shift towards emphasis on individual wellbeing and freedom.”

The following countries ranked under the “Admission” level, which means some of these countries have confirmed policies which admit LGBT people but many in the same group have not confirmed whether or not all LGBT people are permitted to serve:

- France

- Spain

- Germany

- Norway

- Switzerland

- Croatia

- Uruguay

- Argentina

- Austria

- Finland

- Czech Republic

- Portugal

- South Africa

- Brazil

- Bolivia

- Estonia

- Albania

- Ireland

- Hungary

- Cuba

- Japan

Under the “Tolerance” level, which is the middle of the index, these countries generally do not have concrete policies allowing or prohibiting LGBT participation. In some cases, their policies are ambiguous or unpublished:

- Ecuador

- Slovenia

- Colombia

- Luxembourg

- Georgia

- Slovakia

- Chile

- Malta

- Romania

- United States

- Italy

- Poland

- Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Bulgaria

- Latvia

- Lithuania

- Mexico

- Thailand

- Serbia

- Philippines

These “Admission” and “Tolerance” countries offer opportunities for armed forces to lead society in LGBT inclusion or for armed forces to catch up with societies which are already relatively accepting of LGBT people, the report said. Many of these nations have exhibited progress to greater societal acceptance and military inclusion in recent years.

Under the “Exclusion” level, these countries generally have exclusionary policies in the military against members of the LGBT community:

- Peru

- Ukraine

- Vietnam

- Cyprus

- Greece

- Nicaragua

- Nepal

- Rwanda

- Republic of Congo

- Belarus

- Sierra Leone

- China

- Pakistan

- DR Congo

- Lebanon

- Liberia

- Indonesia

- Armenia

- Libya

- Afghanistan

- India

- Qatar

- South Korea

- Russia

- Namibia

- Algeria

- Azerbaijan

- Turkey

- Somalia

Under “Persecution” level, majority of these countries showed signs of LGBT persecution like a legislation that criminalizes LGBT identities:

- Morocco

- Jamaica

- Egypt

- Tanzania

- United Arab Emirates

- Zambia

- Bangladesh

- Belize

- Gambia

- Sudan

- Kazakhstan

- Tunisia

- Malaysia

- Oman

- Cameroon

- Kenya

- Botswana

- Uganda

- Saudi Arabia

- Ghana

- Zimbabwe

- Syria

- Iran

- Nigeria

“Almost all of the countries in the bottom 20 have laws criminalizing sexual activity between consenting adults of the same sex. Some countries sentence to death those who engage in same-sex relations. Countries in the bottom 10 often have public officials who make political claims favoring violence against LGBT individuals. Many of these countries have further laws which attempt to eliminate LGBT identities,” The Hague report said.

According to the report, there were some issues in the differences in policies of countries for LGBT personnel. The policies of one country may undermine the inclusion of LGBT personnel from another. LGBT military personnel may face dangers serving abroad.

The LGBT Military Index revealed that countries vary widely in their approaches to including the LGBT communities to their armed forces. Around 30 countries showed signs of acknowledged LGBT admission but fewer show signs of active engagement with the principle of inclusion.

“Those that are taking active steps to improve inclusion serve as an example of experience and best practice for others interested in LGBT inclusion. These countries are mostly developed, democratic, and located in Europe, the Americas, and Oceania…The close relationship between public acceptance of LGBT people and military inclusion shows the importance of wider societal attitudes, but in cases where military inclusion outpaces public acceptance, the armed forces may be able to lead by example. In contrast, cases where public opinion favors greater inclusion than the military may result in pressure for military reform,” The Hague report said.

“Many countries actively exclude or persecute LGBT people. Wide divergences in policy across countries suggest that policymakers ought to consider the impact on the inclusion of their own LGBT personnel when cooperating with countries that take very different approaches to LGBT people,” it added. —KG/RSJ, GMA Integrated News

Be the first to comment