PA Media

PA MediaTwenty years ago, your music collection consisted of whatever CDs or records you could cram into your bedroom.

Now, anyone with an internet connection has access to more music than they could listen to in one lifetime.

In October 2022, Apple Music boasted its catalogue had reached 100 million songs. Since then, an average of 120,000 new songs have been uploaded every day, making the current total around 176 million tracks.

But here’s the thing: There are still huge gaps.

You can’t stream Ray Charles’ 1977 album True To Life.

Charli XCX’s debut single, !Franchesckaar! has been swallowed by the digital void.

Most important of all, there’s no way to hear 1993’s Christmas number one: Mr Blobby by Mr Blobby.

In fact, one survey by the US Library of Congress suggested that less than 20% of all recorded music was available on the internet.

Sometimes, those recordings are tied up in complex contractual agreements. De La Soul spent two decades clearing the samples on their landmark debut album, 3 Feet High And Rising, before it finally arrived on streaming services last year.

But hundreds of other songs have simply been forgotten.

That’s where Rob Johnson comes in.

By day, he’s a 41-year-old working in business development for a London law firm. By night, he’s a music industry crusader – digging up obscure gems and persuading record labels to make them available online.

Over the last six years, he’s been responsible for 725 releases, including tracks by Sting, Cher and Annie Lennox, with a strong bias for late 90s pop acts such as Billie Piper, S Club and A*Teens.

“I’ll admit it’s a very strange thing to do, but it gives people a lot of happiness so why not?” he tells the BBC.

It all started in 2016, when he helped his friend Jan Johnston – a trance vocalist who’s worked with Paul Oakenfold – to get her catalogue online.

“A lot of her solo music wasn’t out there, simply because it was never a massive hit for the labels,” he recalls.

“So I said to her, ‘OK, this is a hare-brained scheme, but why don’t we contact them and ask them a) do you still own it and b) can you release it?’”

With no industry experience, Johnson simply called the switchboards of the UK’s biggest record companies.

“I hate talking to strangers on the phone, but eventually I got through to the right people and they were like, ‘Yes, we’ll happily put that out’.”

In passing, he suggested to Warner Records that they upload some of Louise Redknapp’s old albums, to capitalise on her appearance on Strictly Come Dancing.

“Good spot,” was the reply.

That’s when he realised this could become a full-time hobby.

“I had a little bit of momentum, so I got bullish and thought, ‘Why don’t I just ask them to release more?’”

To convince the labels, he had to prove there was a demand – so he set up a Twitter account where fans could make requests, calling it Pop Music Activism.

Almost immediately, he was flooded with messages about Victoria Beckham’s debut single, Out Of Your Mind.

“It was slated at the time, but a lot of pop fans looked back retrospectively and thought, ‘That was a bit of a fun bop’,” says Johnson.

After a few calls, he got it uploaded in June 2018, since when it’s amassed 1.8 million streams on Spotify alone.

“The reaction was quite fun,” he says. “You know how gays can be over the top? They were like ‘Oh my God, this has saved my life!’

“And it happened during Pride month, which was a nice little cherry on the cake.”

Rescuing songs takes a lot of work. Contracts have to be checked, original recordings have to be sourced, and streaming services require reams of metadata.

But when it works, artists are thrilled.

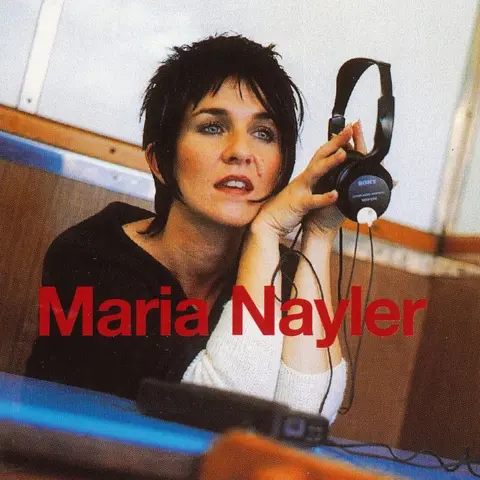

“Rob’s incredible. What he’s done for me, I would do anything for him,” says Maria Nayler.

Known for singing Robert Miles’ 1996 hit One And One, Nayler’s story is a classic tale of music industry misogyny.

After singing on dozens of trance anthems in the 1990s, she was signed to Kylie’s then-label, DeConstruction Records. But when the company found out she was pregnant, it scrapped her debut album.

“They went, ‘We’re not releasing any records while you’re pregnant. It’s gone on the shelf until the baby’s born.’

“Then, of course, nine months down the line, nothing happened.

“In this day and age, they would all be slaughtered, but in the 1990s I just accepted it.”

Johnson was a fan of Nayler’s single Naked and Sacred, and contacted her in 2018 to ask if she wanted help liberating her unreleased material.

“I was a bit like, ‘Who is this guy?’,” she laughs, “but he knew more about my music than I did.”

Sony Music

Sony MusicIt was a tough project. DeConstruction had been bought by BMG, then acquired by Sony, and eventually closed down. No-one was sure who owned Nayler’s master tapes.

“It was a nightmare,” she says. “No-one wanted to talk to Rob.”

Out of options, they sent a blanket email to 75 people at Sony. Within two minutes, the archive team replied and agreed to track down the music.

Nayler’s album, She, was finally released in January 2023. Next month, she goes on tour with dance producer Robert Gillies, who has remixed Naked & Sacred for his next single.

“After all these years and all that hard work, I just feel really, really happy,” she says.

It’s a similar story for Alexis Strum, who was signed and dropped by two major record labels in the early 2000s.

She was left with two fully-completed albums, recorded at a cost of £500,000, that were never released.

“Emotionally, it was huge,” she says. “It’s like having a painting that no-one’s ever seen, or a book that no-one’s ever been allowed to read.”

Some of her unreleased songs were recorded by Kylie Minogue and Rachel Stevens, but a small group of dedicated fans clamoured for the originals.

“Rob told me people had been exchanging my demo CDs on eBay,” she says. “I didn’t even know anyone knew about me!”

With his help, Warner and Universal not only handed over Strum’s masters, but agreed to write off her debts.

Her most popular song Cocoon recently hit 500,000 streams (“half a million more than Universal thought it was going to have”) and, when we speak, she’s back in the studio.

“I’m a mum and I’ve been working in IT, so it’s really weird to be like, ‘I’m going to be a pop star’ again.

“It feels so ridiculous that it’s actually plausible.”

Getty Images

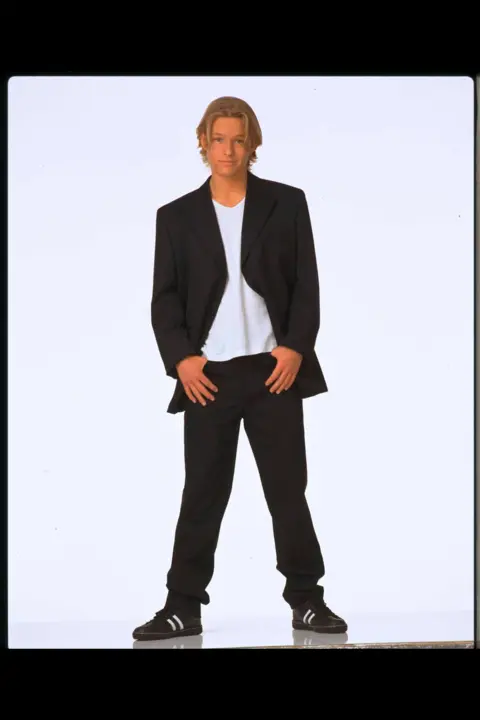

Getty ImagesOne person who’d rather forget their debut album, however, is Adam Rickitt.

The former Coronation Street actor signed a six-album deal with Polydor in 1999, hoping to become the UK’s next teen idol.

“Let’s be honest, I had very little control over the creative side of it,” he laughs.

“They knew what audience I was targeting, and it was the gay audience, the pink pound, and young teenage girls.”

His first single, I Breathe Again, was a massive hit, thanks mainly to a video where he appears completely in the buff, but when subsequent songs missed the top 10, both Polydor and Rickitt lost interest.

His album, Good Time, stalled at number 41 and was, for years, unavailable online.

“I totally understand why I would have slipped through the net,” he laughs. “It’s not exactly like Burt Bacharach disappearing off the face of the earth.”

Unaware of Johnson’s campaign to get the album resurrected, Rickitt was bemused when it sprung back to life in 2018.

“The album period wasn’t my favourite but if people still like it and find it fun, that’s cool. I’m happy with being the retro kitsch guy,” he says.

“But taking me out of the equation, I do think it’s a shame that the record labels can decide what songs people can or can’t listen to.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesJohnson says there’s nothing sinister about these decisions. Catalogue teams with limited resources are obviously going to gravitate towards proven hit songs.

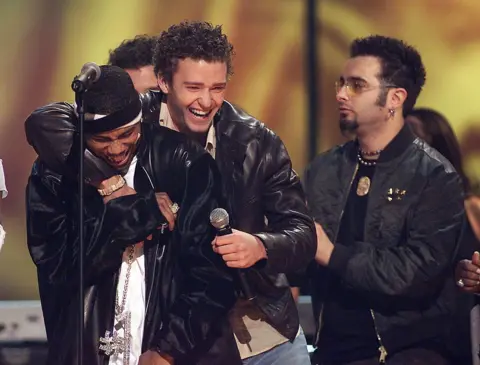

Still, there are blind spots. For a long time, NSync’s single Girlfriend was “greyed out” on Spotify – with the label apparently unaware that the freely-available album version wasn’t the same as the hit remix with Nelly and the Neptunes.

“I picked that one up with Sony US and now that’s getting millions of streams,” says Johnson

It takes a fan to spot these things. And Johnson, who devotes “two to four hours a week” to his project, has just the right mix of passion and affability to nudge labels in the right direction.

“It makes fans happy and it gives artists a sense of closure,” he says, “but it’s also a way of cataloguing music for history.

“Whatever is on Spotify now will migrate onto the services we’ll be using in 10 years, whether that’s a chip in our head, or whatever.”

Be the first to comment