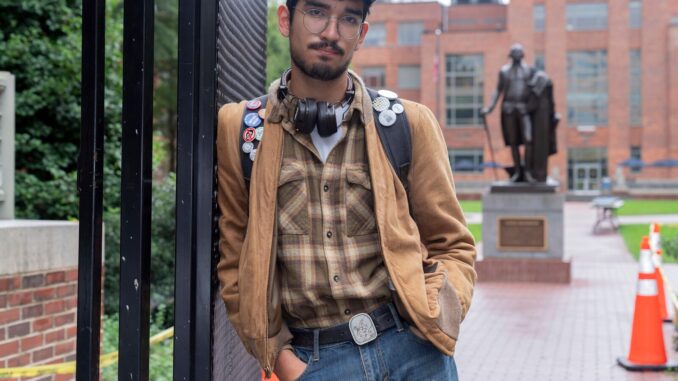

WASHINGTON — As a junior at George Washington University, Ty Lindia meets new students every day. But with the shadow of the Israel-Hamas war hanging over the Washington, D.C., campus, where everyone has a political opinion, each new encounter is fraught.

“This idea that I might say the wrong thing kind of scares me,” said Lindia, who studies political science. “You have to tiptoe around politics until one person says something that signifies they lean a certain way on the issue.”

He has seen friendships — including some of his own — end over views about the war. In public, he keeps his stance to himself for fear that future employers could hold it against him.

“Before Oct. 7, there wasn’t really a big fear,” said Lindia, of Morristown, New Jersey.

A year after Hamas’ attack in southern Israel, some students say they are reluctant to speak out because it could pit them against their peers, professors or even potential employers. Social bubbles have cemented along the divisions of the war. New protest rules on many campuses raise the risk of suspension or expulsion.

Tensions over the conflict burst wide open last year amid emotional demonstrations in the aftermath of the Oct. 7 attack. In the spring, a wave of pro-Palestinian tent encampments led to some 3,200 arrests.

The atmosphere on U.S. campuses has calmed since those protests, yet lingering unease remains.

In a recent class discussion on gender and the military at Indiana University, sophomore Mikayla Kaplan said she thought about mentioning her female friends who serve in the Israeli military. But in a room full of politically progressive classmates, she decided to stay quiet.

“In the back of my head, I’m always thinking about things that I should or shouldn’t say,” Kaplan said.

Kaplan, who proudly wears a Star of David necklace, said that before college she had many friends of different faiths, but after Oct. 7, almost all of her friends are Jewish.

The war began when Hamas-led fighters killed about 1,200 people, mostly civilians, in the Oct. 7 attack on southern Israel. They abducted another 250 people and are still holding about 100 hostages. Israel’s campaign in Gaza has killed at least 41,000 Palestinians, according to the Gaza Health Ministry.

At the University of Connecticut, some students said the conflict doesn’t come up as much in classes. Ahmad Zoghol, an engineering student, said it remains a tense issue and he has heard of potential employers scrutinizing political statements students make in college.

“There’s definitely that concern for a lot of people, including myself, that if we speak about it there’s going to be some sort of repercussion,” he said.

Compared with the much larger campus protests of the Vietnam War era, when few students openly supported the war, campuses today appear more divided, said Mark Yudof, a former president of the University of California system. For many, the issues are more personal.

“The faculty are at odds with each other. The student body is at odds with each other. There’s a war of ideologies going on,” he said.

Some universities are trying to bridge the divide with campus events on civil discourse, sometimes inviting Palestinian and Jewish speakers to share the stage. At Harvard University in Massachusetts, a recent survey found that many students and professors are reluctant to share views in the classroom. A panel suggested solutions including “classroom confidentiality” and teaching on constructive disagreement.

Meanwhile, many campuses are adding policies that clamp down on protests, often banning encampments and limiting demonstrations to certain hours or locations.

At Indiana University, a new policy forbids “expressive activity” after 11 p.m, among other restrictions. Doctoral student Bryce Greene, who helped lead a pro-Palestinian encampment last semester, said he was threatened with suspension after organizing an 11:30 p.m. vigil.

That’s a startling contrast to past protests on campus, including a 2019 climate demonstration that drew hundreds of students without university interference, he said.

“There’s definitely a chilling effect that occurs when speech is being restricted in this manner,” said Greene, who is part of a lawsuit challenging the new policy. “This is just one way for them to restrict people from speaking out for Palestine.”

The tense atmosphere has led some faculty members to rethink teaching certain subjects or entering certain debates, said Risa Lieberwitz, general counsel for the American Association of University Professors.

Lieberwitz, who teaches labor law at Cornell University, has been alarmed by the growing number of colleges requiring students to register demonstrations days in advance.

“It’s so contradictory to the notion of how protests and demonstrations take place,” she said. “They’re oftentimes spontaneous. They’re not planned in the way that events are generally planned.”

Protests have continued on many campuses, but on a smaller scale and often under the confines of new rules.

At Wesleyan University in Connecticut, police removed a group of pro-Palestinian students from a campus building where they held a sit-in in September. Wesleyan President Michael Roth said he supports students’ free speech rights, but they “don’t have a right to take over part of a building.”

Wesleyan is offering new courses on civil disagreement this year, and faculty are working to help foster discussion among students.

“It’s challenging for students, as it is for adults — most adults don’t have conversations with people who disagree with them,” Roth said. “We’re so segregated into our bubbles.”

American universities pride themselves as being places of open discourse where students can engage across their differences. Since Oct. 7, they have been under tremendous pressure to uphold free speech while also protecting students from discrimination.

The U.S. Education Department is investigating more than 70 colleges for reports of antisemitism or Islamophobia. Leaders of several prestigious colleges have been called before Congress by Republicans who accuse them of being soft on antisemitism.

Yet finding the line where protected speech ends is as hard as ever. Leaders grapple with whether to allow chants seen by some as calls of support for Palestinians and by others as a threat against Jews. It’s especially complicated at public universities, which are bound by the First Amendment, while private colleges have flexibility to impose wider speech limits.

At George Washington University, Lindia said the war comes up often in his classes but sometimes after a warming-up period — in one class, discussion loosened after the professor realized most students shared similar views. Even walking to class, there is a visible reminder of the tension. Tall fencing now surrounds University Yard, the grassy space where police broke up a tent encampment in May.

“It’s a place for free expression, and now it’s just completely blocked off,” he said.

Some students say moderate voices are getting lost.

Nivriti Agaram, a junior at George Washington, said she believes Israel has a right to defend itself but questions America’s spending on the war. That opinion puts her at odds with more liberal students, who have called her a “genocide enabler” and worse, she said.

“It’s very stifling,” she said. “I think there’s a silent majority who aren’t speaking.”

___

Associated Press writer Michael Melia in Storrs, Connecticut, contributed to this report.

___

The Associated Press’ education coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

Be the first to comment