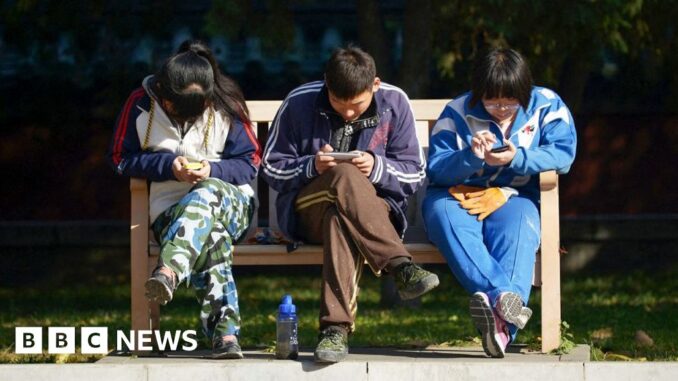

Getty Images

Getty ImagesChina’s sputtering economy has its worried leaders pulling out all the stops.

They have unveiled stimulus measures, offered rare cash handouts, held a surprise meeting to kickstart growth and tried to shake up an ailing property market with a raft of decisions – they did all of this in the last week.

On Monday, Xi himself spoke of “potential dangers” and being “well-prepared” to overcome grave challenges, which many believe was a reference to the economy.

What is less clear is how the slowdown has affected ordinary Chinese people, whose expectations and frustrations are often heavily censored.

But two new pieces of research offer some insight. The first, a survey of Chinese attitudes towards the economy, found that people were growing pessimistic and disillusioned about their prospects. The second is a record of protests, both physical and online, that noted a rise in incidents driven by economic grievances.

Although far from complete, the picture neverthless provides a rare glimpse into the current economic climate, and how Chinese people feel about their future.

Beyond the crisis in real estate, steep public debt and rising unemployment have hit savings and spending. The world’s second-largest economy may miss its own growth target – 5% – this year.

That is sobering for the Chinese Communist Party. Explosive growth turned China into a global power, and stable prosperity was the carrot offered by a repressive regime that would never loosen its grip on the stick.

Bullish to bleak

The slowdown hit as the pandemic ended, partly driven by three years of sudden and complete lockdowns, which strangled economic activity.

And that contrast between the years before and after the pandemic is evident in the research by American professors Martin Whyte of Harvard University and Scott Rozelle of Stanford University’s Center on China’s Economy.

They conducted their surveys in 2004 and 2009, before Xi Jinping became China’s leader, and during his rule in 2014 and 2023. The sample sizes varied, ranging between 3,000 and 7,500.

In 2004, nearly 60% of the respondents said their families’ economic situation had improved over the past five years – and just as many of them felt optimistic about the next five years.

The figures jumped in 2009 and 2014 – with 72.4% and 76.5% respectively saying things had improved, while 68.8% and 73% were hopeful about the future.

However in 2023, only 38.8% felt life had got better for their families. And less than half – about 47% – believed things would improve over the next five years.

Meanwhile, the proportion of those who felt pessimistic about the future rose, from just 2.3% in 2004 to 16% in 2023.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhile the surveys were of a nationally representative sample aged 20 to 60, getting access to a broad range of opinions is a challenge in authoritarian China.

Respondents were from 29 Chinese provinces and administrative regions, but Xinjiang and parts of Tibet were excluded – Mr Whyte said it was “a combination of extra costs due to remote locations and political sensitivity”. Home to ethnic minorities, these tightly controlled areas in the north-west have long bristled under Beijing’s rule.

Those who were not willing to speak their minds did not participate in the survey, the researchers said. Those who did shared their views when they were told it was for academic purposes, and would remain confidential.

Their anxieties are reflected in the choices that are being made by many young Chinese people. With unemployment on the rise, millions of college graduates have been forced to accept low-wage jobs, while others have embraced a “lie flat” attitude, pushing back against relentless work. Still others have opted to be “full-time children”, returning home to their parents because they cannot find a job, or are burnt out.

Analysts believe China’s iron-fisted management of Covid-19 played a big role in undoing people’s optimism.

“[It] was a turning point for many… It reminded everyone of how authoritarian the state was. People felt policed like never before,” said Alfred Wu, an associate professor at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy in Singapore.

Many people were depressed and the subsequent pay cuts “reinforced the confidence crisis,” he added.

Moxi, 38, was one of them. He left his job as a psychiatrist and moved to Dali, a lakeside city in southwestern China now popular with young people who want a break from high-pressure jobs.

“When I was still a psychiatrist, I didn’t even have the time or energy to think about where my life was heading,” he told the BBC. “There was no room for optimism or pessimism. It was just work.”

Does hard work pay off? Chinese people now say ‘no’

Work, however, no longer seems to signal a promising future, according to the survey.

In 2004, 2009 and 2014, more than six in 10 respondents agreed that “effort is always rewarded” in China. Those who disagreed hovered around 15%.

Come 2023, the sentiment flipped. Only 28.3% believed that their hard work would pay off, while a third of them disagreed. The disagreement was strongest among lower-income families, who earned less than 50,000 yuan ($6,989; £5,442) a year.

Chinese people are often told that the years spent studying and chasing degrees will be rewarded with financial success. Part of this expectation has been shaped by a tumultuous history, where people gritted their teeth through the pain of wars and famine, and plodded on.

Chinese leaders, too, have touted such a work ethic. Xi’s Chinese Dream, for example, echoes the American Dream, where hard work and talent pay off. He has urged young people to “eat bitterness”, a Chinese phrase for enduring hardship.

But in 2023, a majority of the respondents in the Whyte and Rozelle study believed people were rich because of the privilege afforded by their families and connections. A decade earlier, respondents had attributed wealth to ability, talent, a good education and hard work.

This is despite Xi’s signature “common prosperity” policy aimed at narrowing the wealth gap, although critics say it has only resulted in a crackdown on businesses.

There are other indicators of discontent, such as an 18% rise in protests in the second quarter of 2024, compared with the same period last year, according to the China Dissent Monitor (CDM).

The study defines protests as any instance when people voice grievances or advance their interests in ways that are in contention with authority – this could happen physically or online. Such episodes, however small, are still telling in China, where even lone protesters are swiftly tracked down and detained.

A least three in four cases are due to economic grievances, said Kevin Slaten, one of the CDM study’s four editors.

Starting in June 2022, the group has documented nearly 6,400 such events so far.

They saw a rise in protests led by rural residents and blue-collar workers over land grabs and low wages, but also noted middle-class citizens organising because of the real estate crisis. Protests by homeowners and construction workers made up 44% of the cases across more than 370 cities.

“This does not immediately mean China’s economy is imploding,” Mr Slaten was quick to stress.

Although, he added, “it is difficult to predict” how such “dissent may accelerate if the economy keeps getting worse”.

How worried is the Communist Party?

Chinese leaders are certainly concerned.

Between August 2023 and Janaury 2024, Beijing stopped releasing youth unemployment figures after they hit a record high. At one point, officials coined the term “slow employment” to describe those who were taking time to find a job – a separate category, they said, from the jobless.

Censors have been cracking down on any source of financial frustration – vocal online posts are promptly scrubbed, while influencers have been blocked on social media for flaunting luxurious tastes. State media has defended the bans as part of the effort to create a “civilised, healthy and harmonious” environment. More alarming perhaps are reports last week that a top economist, Zhu Hengpeng, has been detained for critcising Xi’s handling of the economy.

The Communist Party tries to control the narrative by “shaping what information people have access to, or what is perceived as negative”, Mr Slaten said.

Moxi

Moxi CDM’s research shows that, despite the level of state control, discontent has fuelled protests – and that will worry Beijing.

In November 2022, a deadly fire – which killed at least 10 people who were not allowed to leave the building during a Covid lockdown – brought thousands onto the streets in different parts of China to protest against crushing zero-Covid policies.

Professors Whyte and Rozelle don’t think their findings suggest “popular anger about… inequality is likely to explode in a social volcano of protest.”

But the economic slowdown has begun to “undermine” the legitimacy the Party has built up through “decades of sustained economic growth and improved living standards”, they write.

The pandemic still haunts many Chinese people, said Yun Zhou, a sociology professor at the University of Michigan. Beijing’s “stringent yet mercurial responses” during the pandemic have heightened people’s insecurity about the future.

And this is particularly visceral among marginalised groups, she added, such as women caught in a “severely discriminatory” labour market and rural residents who have long been excluded from welfare coverage.

Under China’s contentious “hukou” system of household registration, migrant workers in cities are not allowed to use public services, such as enrolling their children in government-run schools.

But young people from cities – like Moxi – have flocked to remote towns, drawn by low rents, picturesque landscapes and greater freedom to chase their dreams.

Moxi is relieved to have found a slower pace of life in Dali. “The number of patients who came to me for depression and anxiety disorders only increased as the economy boomed,” he said, recalling his past work as a psychiatrist.

“There’s a big difference between China doing well, and Chinese people doing well.”

About the data

Whyte, Rozelle and Alisky’s research is based on four sets of academic surveys conducted between 2004 and 2023.

In-person surveys were conducted together with colleagues at Peking University’s Research Center on Contemporary China (RCCC) in 2004, 2009 and 2014. Participants ranged in age from 18-70 and came from 29 provinces. Tibet and Xingiang were excluded.

In 2023, three rounds of online surveys, at the end of the second, third and fourth quarters, were conducted by the Survey and Research Centre for China Household Finance (CHFS) at Southwestern University of Finance and Economics in Chengdu, China. Participants ranged in age from 20-60.

The same questions were used in all surveys. To make responses comparable across all four years, the researchers excluded participants aged 18-19 and 61-70 and reweighted all answers to be nationally representative. All surveys contain a margin of error.

The study has been accepted for publication by The China Journal and is expected to be published in 2025.

Researchers for the China Dissent Monitor (CDM) have collected data on “dissent events” across China since June 2022 from a variety of non-government sources including news reports, social media platforms operating in the country and civil society organisations.

Dissent events are defined as instances where a person or persons use public and non-official means of expressing their dissatisfaction. Each event is highly visible and also subject to or at risk of government response, through physical repression or censorship.

These can include viral social media posts, demonstrations, banner drops and strikes, among others. Many events are difficult to independently verify.

Charts by Pilar Tomas of the BBC News Data Journalism Team

Be the first to comment