MANILA, Philippines — Matt Lazatin was scrolling through his phone one morning when a loud thud echoed through the house, as if something had slammed against a window.

Lazatin scrambled to his feet to check the scene. Looking through one of the glass doors of his living room, he saw a limping chestnut munia — a small reddish-brown bird with a black head and a short white beak.

The bird, locally known as mayang pula, was stunned on the ground as it tried to regain its senses. Wary of stray cats that could pounce anytime, Lazatin quietly watched as the bird recovered its strength before flying away.

This incident — which took place in his family home in Pampanga in 2021 — was not the last.

“There have been at least three different instances, usually in the same spot,” said Lazatin, a biology graduate student at the Ateneo de Manila University.

Matt Lazatin

On one occasion, it was another chestnut munia, whom he rushed to place in a shoebox with a makeshift bed made of paper towels.

In another instance, it was the much larger zebra dove that slammed into the window, dying on impact.

The series of bird-window strikes that Lazatin witnessed is a widespread threat to avian populations globally, including in the Philippines. Yet public awareness about these collisions remains low, adding to the threats that birds already face amid dwindling natural habitats and increasing human encroachment.

In the United States alone, at least 1.2 billion birds die annually due to window collisions, according to a 2024 study in the Wilson Journal of Ornithology. There are potentially billions more dying globally every year from these crashes.

The Philippines – home to over 700 species of birds, including 205 that are endemic – is not spared from bird-window collisions.

Concerned citizens who report bird window strikes to the Facebook group Birdwatch Philippines Community have helped to track these events.

Citizen science in action

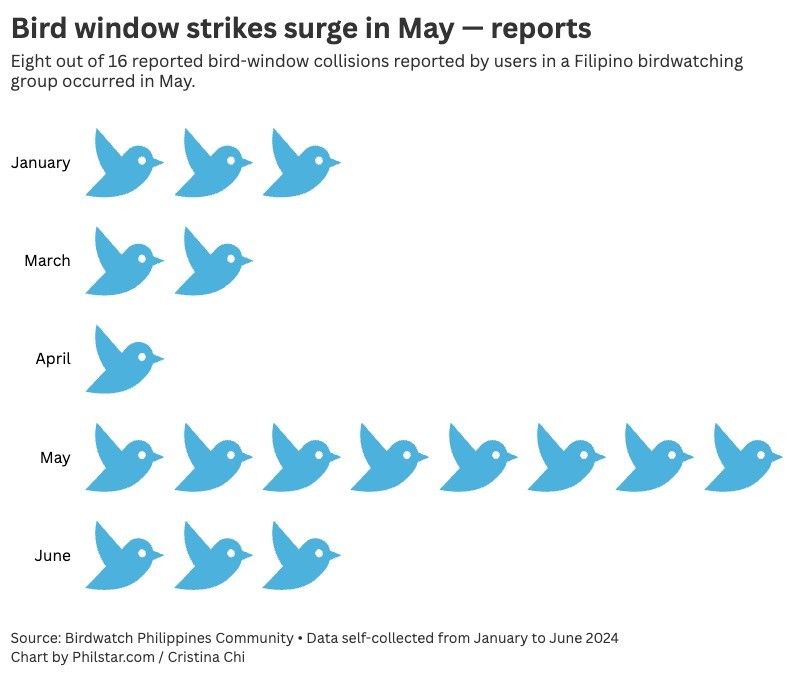

Search results for keywords like “hit,” “bumangga (collided),” “window,” and “bintana (window)” in the Facebook group show at least 17 likely incidents reported from January to June this year

A manual search in an online Filipino birdwatching community shows 16 posts of potential bird-window collisions published in 2024 so far, with half reported in May.

A resident from Davao saw two collisions involving a northern boobook in January and a yellow-breasted fruit dove in March. Both birds fortunately survived. Another uploaded a photo of a dead common emerald dove in Batangas and curiously wrote, “Why would these birds kill themselves by banging themselves on a window glass?”

Those in the comment sections often notified the Facebook page Bird Window Strike PH (BWS PH), whose page administrator would tell the post author to expect a private message from the team.

Founded by scientists Janina Castro and Jelaine Gan, BWS PH collects citizen data to understand the local occurrence of bird-window collisions, an issue “relatively new” to the Philippines, the former said.

Castro traced the roots of the project to a stunned coppersmith barbet that her friend found on the Ateneo campus in 2017. Not knowing what to do, they turned over the bird to a college wildlife organization.

“After that, I realized that window strikes are studied in other countries, but not yet in the Philippines,” said Castro, now a science communication graduate student in New Zealand. “I saw that people would post about it on Facebook, on Instagram, but there’s actually no data collection happening.”

She began logging details of bird-window strikes from social media posts and reports that she observed. She later invited Gan, a birder and a then-biology student at the University of the Philippines (UP) Diliman, to form a “little side project.”

As a citizen science initiative, BWS PH relies on data from collisions witnessed by the public. The pair takes into account different details, such as species of the bird, date, time and height of collision, and window measurements.

“These are reports by normal everyday people who happen to see a bird hit a window in their homes, schools, or offices,” said Gan.

Steps to take post-window strike. According to BWS PH, those who encounter possible bird-window strikes should first assess the well-being of the avian victim.

Some birds fly away unscathed after the collision, but others sustain injuries and trauma. In such cases, the injured bird must be housed in a dark and enclosed area to avoid being eaten by cats and other animals. People should also avoid feeding or giving water to the bird to avoid choking.

Once the bird regains its strength, it can be released back to the area where it was found. Otherwise, it should be taken to the nearest specialist.

In unfortunate cases leading to the bird’s death, its carcass may be wrapped in plastic and donated to research centers, such as the vertebrate museum of UP Diliman’s Institute of Biology.

Extent of collisions

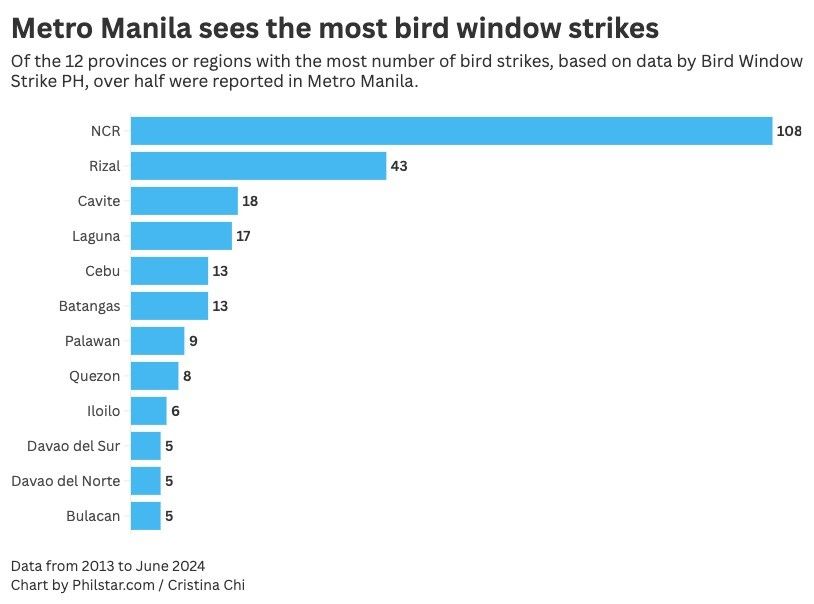

As of June 2024, the BWS PH has gathered 338 reports of bird-window strikes nationwide, including 108 incidents in Metro Manila, 43 in Rizal, and 18 in Cavite. Metro Manila had the most number of reported strikes.

Top 12 provinces / regions with bird strikes from 2013 to June 2024, according to data from Bird Window Strike PH

BWS PH, however, said they cannot claim that Metro Manila has the most collisions, explaining that the rank may only be due to the residents’ high access to the internet and the likelihood of seeing their social media posts online.

While UP Diliman and Ateneo also appear as two hotspots when mapping the collected strikes, Gan said the two schools could be “just more engaged” in the community.

“We’re not yet at the point where we’re saturated with enough data [to explain their occurrences in the Philippines],” said Gan, who is currently pursuing her doctorate in biology in the United Kingdom.

Even if exact numbers are difficult to pin down, one thing is clear: reflective surfaces like windows are the leading cause of bird collisions, said Paulo Miguel Kim, a herpetologist and biodiversity expert from UP Diliman.

Windows reflect the sky and trees, making them enticing areas for birds to fly into. As birds swoop towards these illusions, they suddenly realize too late that they’re about to hit a solid pane of glass.

Lieniel Gabuni

Timmy Romero/Courtesy of Bird Window Strike PH

Some birds more vulnerable than others

The coppersmith barbet that Castro’s friend saw was one of the most common bird strike victim species that BWS PH calls “super-colliders.” Current data from the team revealed that this category include doves, pigeons, kingfishers, pittas, sparrows, and barbets.

Among these super-colliders, the urban-dwelling common emerald dove was involved in a staggering 72 collision reports, 54 more than the trailing hooded pitta. Still, given the limitations of the team’s data, these findings may not show the full picture.

Cromwell Oliver Hernandez

Carmela Española, an ornithologist from UP Diliman, said that a possible reason behind the high number of bird strikes among common emerald doves was that they fly low and fast.

“The victims are usually flying really fast and they have long wings, like the migratory birds,” she said. “But if their wings are short and rounded, they’re good at avoiding obstacles when they fly.”

Birds are important indicators of the environment’s health, stability, and sustainability. Española said they help maintain the balance of an ecosystem by controlling the population of pests and prey and by propagating plants through pollination and seed dispersal.

But as more birds fall prey to society’s ornamental designs, the balance so desperately needed in nature falls as well.

For humans to promote coexistence and biodiversity, each person must be knowledgeable of the environment’s fragility, Kim said.

“You have to change the mindset of an entire city to do that,” said Kim. “I think it all starts with awareness.”

Mike Go, a resident of Tanay, Rizal, was also unfamiliar with bird-window collisions, until he encountered an injured guaiabero, a species of parrot, outside the window of one of his vacation rentals.

Go turned to the birders and BWS PH for help.

Avoiding bird strikes

One way to avoid bird strikes, according to BWS PH, is to break up the reflections of the sky on windows by installing stickers at least one centimeter in size and placing them five centimeters apart.

These specifically designed stickers, however, can be “quite expensive,” costing around P880, and are sourced from an international company, said Gan.

Due to the high cost and limited availability of window stickers, he decided to create his own using a cheap sticker roll he purchased online. Go cut it into tiny pieces and placed them one by one on all windows—a process he described as “tedious but worth it.”

Mike Go

“For me, the graphics [of the windows after applying stickers] are not ugly. It’s normal. It’s worth it if it will save the birds,” Go added.

None of his cottages recorded a single bird strike incident after installing window stickers, he said.

Hanneke Thieme, a frequent reporter of bird strikes, used strings to break up the pattern of reflective windows in their house in San Mateo, Rizal.

Hanneke Thieme

“The strings are installed around one to three meters from the window so that the birds have time to stop or turn around,” Thieme said.

Other do-it-yourself solutions include hanging ropes or putting up a mesh outside of the reflective surfaces, said Castro.

Society-level solutions

Individual efforts, however, can only do so much. The Philippines has yet to create any laws or local ordinances that will mitigate bird-window collisions at a larger scale.

In the United States, New York and San Francisco have adopted bird-friendly building design standards and construction requirements.

Urban planner Gabby Lopez said the National Building Code of the Philippines needs to be updated to help address these collisions. Enacted in 1977, the current code does not include any provisions addressing these.

He also suggested creating zoning ordinances at the local government units first before pushing for national legislation.

For bird expert Española, incorporating bird-friendly designs in urban planning should be done from the onset.

“At the planning stage of the house or building, they should make sure that there are very few glass windows or doors because it’s not bird-friendly,” she said. “Prevention is better than cure.”

—

Editor’s Note: Charmaine Estabas, Lieniel Gabuni and Anj Guillermo are journalism students from the University of the Philippines Diliman. This report was their final project under their Journalism 112 (Reporting on the Environment) class.

Be the first to comment