Getty Images

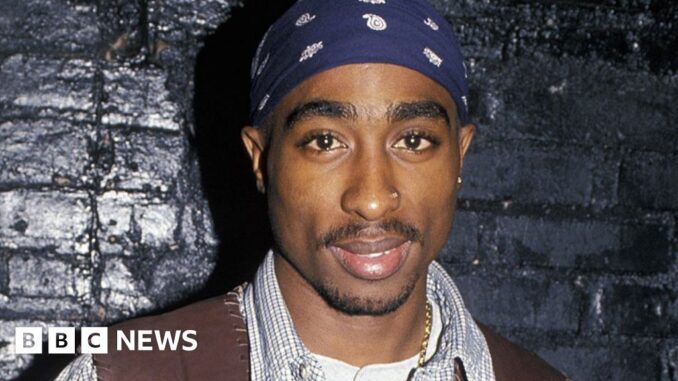

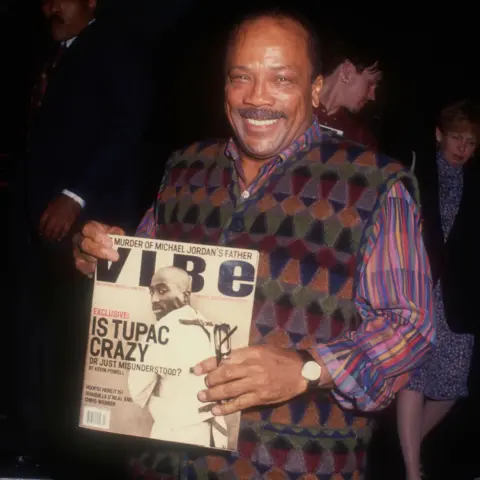

Getty ImagesBefore the east and west coast rap beef of the 1990s boiled over with the murders of Tupac Shakur and Notorious BIG, legendary producer Quincy Jones called a secret meeting at which he appealed for an end to the violence.

As hip-hop rose from the streets to the mainstream in the 90s, the rappers and hustlers that broke through had few role models who had trodden that path before them.

There was one man, though, who had been there, and done pretty much everything.

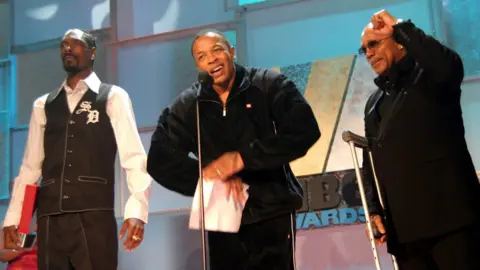

Quincy Jones had been in gangs and had been stabbed at the age of seven in 1930s Chicago, before becoming a major force in American music thanks to his work with legends like Ray Charles, Frank Sinatra and Michael Jackson.

He was at the heart of revolutions in jazz, swing, soul, funk, disco and pop – but one aspect of his career that got less attention when he died last week at the age of 91 was his place in hip-hop.

Madison McGaw/BFA.com/Shutterstock

Madison McGaw/BFA.com/ShutterstockJones was revered in all corners of music, including rap. Unlike most in the old guard and the media, he immediately realised the scene’s artistic and cultural importance.

Hip-hop reminded him of the bebop jazz of his youth. “I feel a kinship there because we went through a lot of the same stuff,” he said.

“Quincy understood it and got it right away,” says pioneering artist, rapper and presenter Fab 5 Freddy.

Jones worked with leading rappers in the 80s, and in the 90s he recognised risks including a volatile rivalry that had begun to erupt between competing labels and stars.

So he brought artists, executives and elder black American statesmen together for a secret summit in 1995, hoping it would be a turning point.

Getty Images

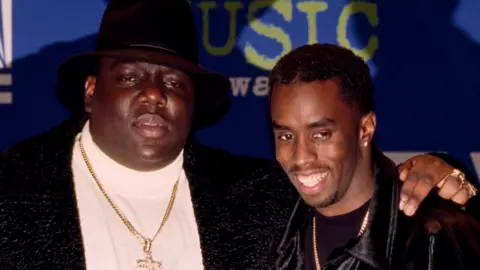

Getty ImagesThe east coast was hip-hop’s spiritual home. In 1992, Sean Combs – then known as Puffy and later as P Diddy – launched his Bad Boy record label in New York with artists including Notorious BIG, aka Biggie Smalls.

Meanwhile, across America, Los Angeles was coming into its own as the capital of gangsta rap, led by menacing mogul Suge Knight’s Death Row Records, which had Dr Dre and Tupac.

In 1994, Tupac was shot and injured during a robbery in the lobby of a studio. He later implied that his former friend Biggie may have known about the attack in advance. Biggie then released the track Who Shot Ya?, which Tupac thought was about him.

The beef continued at the Source magazine awards on 3 August 1995, when Knight goaded Combs and Bad Boy Records from the stage.

Jones, who had his own magazine, Vibe, held his summit three weeks later.

The brewing east-west beef wasn’t the only reason Jones called it – it was mainly intended to discuss the state of hip-hop and let the new generation hear life and business advice from a group of highly successful black executives.

But rap’s negative image and the burgeoning tensions were a big talking point.

“He knew this was a bubbling issue, and so his idea was to bring together a symposium,” says Fab 5 Freddy, who was hosting Yo! MTV Raps at the time and was the event’s moderator.

Jones told the summit: “The thing that really provoked me to say it’s time to pay attention now is Tupac.”

Tupac was missing, however – he was in jail for sexual assault at the time. Suge and Dre were there, as were Combs and Biggie.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesJones had already experienced his own beef with Tupac – the rapper criticised the producer in a 1993 edition of Source for marrying white women.

“We finally hooked up, even though it was tension conditions in the beginning,” Jones said at the event.

“We finally talked to each other, and he said nobody had talked to him like that before.

“And I said, I can’t take it any more. Because we can no longer afford to be non-political, and I’m talking to the hip-hop nation now.”

Alamy

AlamyAbout 50 influential artists and executives were in the room, including Public Enemy’s Chuck D, members of A Tribe Called Quest, MC Lyte, Kris Kross, Jermaine Dupri and Boyz n the Hood film-maker John Singleton.

Jones wrote in his now-out-of-print 2001 autobiography: “I had been concerned about the potentially volatile diversity of a group who’d never been in the same room together.”

They were joined by veteran executives Clarence Avant and Ahmet Ertegun, plus Colin Powell, the former national security adviser and head of the US military who would go on to become the first African-American secretary of state.

Powell had presidential ambitions – that was why the summit was held in secret. Jones wanted to save Powell from being associated with the negative publicity that surrounded rap music.

He switched venues at the last minute to throw press off the scent, and confiscated the recordings.

“Rest assured that my discretion is based on a deep respect for you and a valued friendship,” Jones wrote to Powell in an unpublished letter held at Indianapolis University Library.

“I know that we are going to make a difference at this conference. Thanks for the way you handled the situation. Maybe we can turn the battleship an inch or two.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesJones later wrote in his book: “Some of the younger rappers didn’t even know who he was. When addressing some of the more confrontational comments from the floor, Powell maintained his South Bronx demeanour and authoritative cool throughout.”

Fab 5 Freddy remembers one exchange between Powell and Knight. “There was an encounter where he [Knight] had something to say, and Colin Powell responded.

“Here you have this guy who was a four-star general talking to Suge Knight, and he pretty much put Suge in his place.”

Jones finally released a clip of the event for a 2018 Netflix documentary about his life.

“We’ve got to seriously talk about what you are going to deal with,” he is seen telling the assembled attendees.

“They are not playing, there’s real bullets out there, believe me. Maybe literally and figuratively.

“It’s a very emotional thing,” he added, his voice cracking. “I want to see you guys live to at least my age.”

“Quincy did get emotional,” Fab 5 Freddy recalls, “because he sensed what could happen.

“And the worst, unfortunately, did happen.”

Jones had ended up reconciling with Tupac. After Tupac’s 1993 comments, Jones’s 17-year-old daughter Rashida – who would go on to star in US sitcom The Office – wrote an irate letter to Source attacking the rapper.

When Tupac bumped into one of Jones’s other daughters, Kidada, he apologised, thinking she was Rashida. But Tupac and Kidada hit it off and began a relationship.

“Though we got off to a rocky start, as I came to know and feel him I saw his enormous potential and sensitivity as an artist and as a human being,” Quincy Jones wrote.

There have also been claims that Tupac was planning to leave Death Row for Jones’s record label.

But in September 1996, a year after the summit, Tupac was shot and killed.

A former gang leader, Duane “Keffe D” Davis, was charged with his murder last year. He has pleaded not guilty.

Then in 1997, Notorious BIG was shot dead outside a party thrown by Jones’s record label and magazine. No-one has ever been charged.

Meanwhile, today Knight is in prison for a hit-and-run, while Combs is awaiting trial on charges of racketeering and sex trafficking, which he denies.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe violence in the 90s “wasn’t necssary” and was caused by “wannabes and gang-related troublemakers” on the edges of the music industry, according to Fab 5 Freddy.

“Also, the east/west coast beef was mainly ignited by jealousy. It was an ashtray fire fanned into a big deal by media outlets that led to Biggie and Tupac getting killed.”

Despite his stature, not even Jones could alter the forces of power and pride that were at work and prevent the bloodshed.

Freddy believes some lessons were learned at the summit, however, and that it deserves a place in hip-hop history.

“It was incredible and electric to be in that room.

“It was a thrilling moment. And then it became even more legendary because it was never released, so the only people that really knew about it were the people that were there.”

Be the first to comment