LEEROY New’s works defy containment. Known for his large-scale immersive installations, he transmogrifies the built environment with his culturally modified spaces. He describes the current direction of his art as “architectural, relational, real — beyond fictional.”

Thus, it was not surprising that his work went beyond featuring collectible and demure objects during “Woven Stories,” one of the culminating events of Design Week 2024 at the Cultural Center of the Philippines (CCP) Black Box.

Artist Leeroy New

What characterizes New’s installations is their monumentality, which he believes should not be the sole cache of first-world artists. “As a child, I watched sci-fi movies,” he said. “I have always wanted to recreate the giant sets, over-the-top costumes, and prosthetics.”

Recent works like the “Mebuyan’s Vessel” (San Juan La Union, Philippines 2020), “Balete, Bulate, Bituka” (The Bentway, Toronto, 2023), and “Night Feast” (Brisbane, Australia, 2024) can be classified as massive public art with intentions of interactivity. His prodigious pieces, like “Floating Island Project” (2015), aim to upcycle the environment that has become degraded or abandoned.

In his projects, designing the building is a single beat in a whole process involving education and multi-stakeholder engagement, including the host community, fellow architects, engineers and security people. Yet, to construe him as cosmopolitan might be a mistake.

Born in 1986, he hails from a Filipino-Chinese family (his surname New is Hokkien) from General Santos. This self-described “quiet boy from Mindanao also learned from my theater arts classmates how to communicate to different stakeholders … how to make them see what was still germinating in my imagination.”

A palpable influence is Robert Feleo, whose words New echoes in all his talks: “Before we are painters and sculptors, Filipinos are weavers, potters, and carvers.”

Feleo, who used sawdust as material and developed singular techniques called “pinalakpak” and “sapin-sapin,” helped set New off on a quest for materials other than oil and wood. This phase was built on New’s training at the National High School for the Arts and the University of the Philippines (UP) Fine Arts, where he rummaged for alternatives to Western forms and materials.

The training also made him look for alternatives to art-sanctioned spaces during his lean years. New recalled, “When no gallery wanted to represent us, I pretended to be a volunteer artist for the Metropolitan Manila Development Authority (MMDA), and painted on the walls on EDSA.”

Mebuyan’s Vessel, San Juan, La Union, 2020. PHOTOS FROM LEEROY NEW

Reminiscent of the practice of national artists Rolando Tinio and Salvador Bernal in their production designs, New would go to Divisoria to buy toys, halo-halo glasses, and food covers by the kilo to come up with materials that can have a counter-narrative in the contemporary Filipino art scene. He looked to local aesthetic practices like the “pahiyas” and Christmas-tree-making contests in the rural areas as “inherent forms of installation.”

Environmental solutions

His works arise from what he dubs “the aesthetics of the fiesta,” pouring out of an “outrageous celebration, a confluence of fertility, abundance, and community.” Rather than of poverty and scarcity, his employment of the excesses of production — oodles of knitting needles, salad spinners, baskets and anahaw fans — speaks of generosity and hospitality.

This design philosophy explains the metamorphoses of the found objects into trees and natural bamboo into spaceships. He experiments with water bottles, regarded as one of the most environmentally menacing products, to imagine creative solutions to plastic pollution.

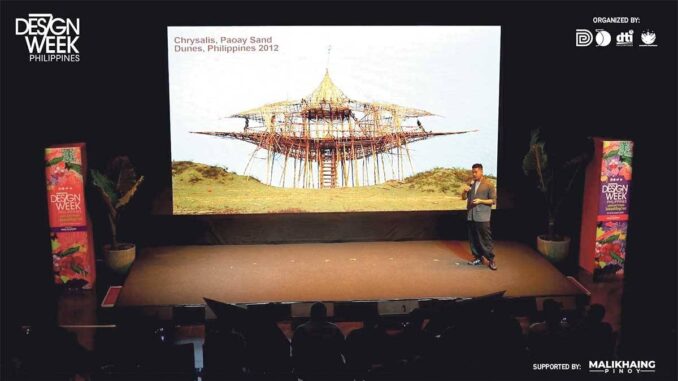

Chrysalis, Paoay Sand Dunes, 2012.

Dreams of flying into distant planets have been used to solve environmental problems. He has built domes with oversized blue water bottles, experimenting with their possible use as roofing and wall cladding.

Still, finding solutions to the water bottle problem, as well as to other synthetic products, has been a challenge for designers. These bottles, when they end up in the ocean, kill 1.1 million marine animals annually. One possible solution is upcycling and reusing them for art and design. New spends half his time abroad, where he converts materials into local recycling and repurposes them into works of art.

The 38-year-old artist also plans to build his local studio. Amidst what he believes is the scarcity of waste management infrastructures, he will replicate in Manila a facility where people can bring recyclable items that artists can buy to use as materials for their works. This, too, may be a path to longevity and sustainability. As art school taught him, “Art in the Philippines is a 24/7 disaster response.”

Be the first to comment