MANILA, Philippines — In the pantheon of Filipino heroes, women are few and far between. They can be counted on the fingers of one hand – the bolo-wielding Gabriela Silang, the KKK’s lakambini Gregoria de Jesus and the flag-maker Marcela Agoncillo.

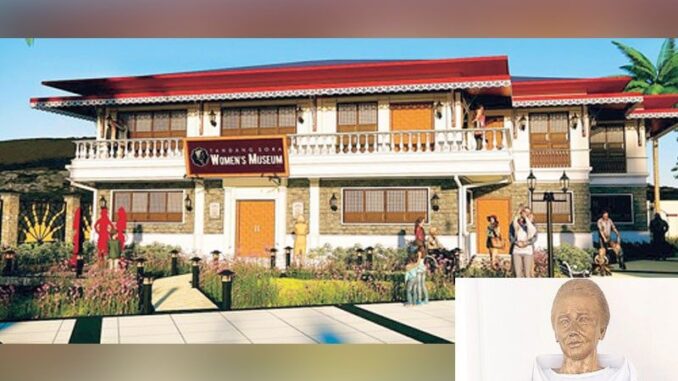

Then there is the beloved Tandang Sora, who is best-known as the mother-figure of the Philippine Revolution and lately, the heroine of Quezon City.

The birthday of Tandang Sora, otherwise known as Melchora Aquino, is celebrated every Jan. 6, the traditional Feast of the Three Kings. She was, after all, named after Melchor, the oldest of the Magi and the bearer of the gift of gold to the Infant Jesus.

Textbooks and historical markers say that she was born in the year 1812.

New research by Katipunan scholar Dr. Jim Richardson, however, showed that her true birth year was some 24 years later, or in 1836 – and, therefore, that she was not that old, after all.

“A tax list of residents (or vecindario) for Cabeceria No. 6, Pueblo de Caloocan, 1876, filmed at the Bureau of Public Records (now the National Archives) by the Genealogical Society of Utah in 1979 and now accessible online at Family Search, proves the 1812 year to be wrong,” Richardson wrote.

If the 1812 date were correct, then that would put her at the ripe old age of 84 at the start of the Philippine Revolution in August 1896.

As every schoolboy knows, it was Tandang Sora that fed the Katipunan army, led by Andres Bonifacio, as they mustered their forces before their first encounter with the Spanish Guardia Civil.

Tandang Sora opened her ample bodega to more than a thousand Katipuneros, emptying “all of her storehouse of 100 cavans, and all her cattle, carabaos, chickens and pigs,” according to accounts.

Indeed, one report of the time described the Katipuneros feasting on sinigang na kalabaw. (There was a tall sampaloc tree near the battleground-to-be.)

But who exactly was Tandang Sora?

Baptized as Melchora Aquino, she would marry an enterprising farmer by the name of Fulgencio Ramos, who was a cabeza de barangay or village chief.

Their farmland would be in Banlat, around the vicinity of today’s Tandang Sora Avenue, which once formed part of the Piedad friar estate.

Heading the tax list of residents for that village in 1876 was Ramos, honored, according to Richardson, with the title “Don” because he was the community’s head.

Ramos’ age was given as 40 years old.

Aquino follows on the next line below him, and is also listed as age 40 with the title “Doña” as the cabeza’s wife.

This would make her birthyear 1836, putting her at the more reasonable age of 60 at the start of the Philippine Revolution in 1896.

Eyewitness accounts describe her, in fact, as pandak at mataba, or short and stout, and also in her midlife, but still strong enough to help with the grinding of the provisions of rice.

Richardson noted that this record was not an isolated case.

Subsequent documents listed her progressing yearly into her fifties.

The tax list for 1896 actually gave her age at 56, which was not consistent with the 1876 list.

Such minor variations are common in the vecindarios, but never drastic discrepancies as wide as 24 years.

Their six children were listed in order of their ages in 1876: Juan Ramos, the oldest, listed as 21 years of age and her youngest, Juana, listed as three years old.

If textbooks and markers are correct in saying that Tandang Sora was born in 1812, Richardson emphasized that “she must have given birth to her first child at the age of 43 and to her last when she was 61 – a pattern of child-bearing that has not been recorded anywhere then or since.”

What is more plausible is that she was 19 when she gave birth to Juan and 37, to her youngest.

The source of the confusion seems to have been Tandang Sora’s death certificate in 1919, which gave her age as an astounding 107 years, “but that is clearly inaccurate,” according to Richardson.

Tandang Sora was probably closer to the more believable age of 83.

For her sacrifices for the nation, Tandang Sora was among those first rounded up by the Spanish after the Katipunan’s first encounter, which was fought near her farm on Aug. 26, 1896.

She would be sentenced to imprisonment in Guam, but would be released by the Americans and returned home in 1903.

Be the first to comment