BBC

BBCThey are the bête noire of many nutritionists – mass-produced yet moreish foods like chicken nuggets, packaged snacks, fizzy drinks, ice cream or even sliced brown bread.

So-called ultra-processed foods (UPF) account for 56% of calories consumed across the UK, and that figure is higher for children and people who live in poorer areas.

UPFs are defined by how many industrial processes they have been through and the number of ingredients – often unpronounceable – on their packaging. Most are high in fat, sugar or salt; many you’d call fast food.

What unites them is their synthetic look and taste, which has made them a target for some clean-living advocates.

There is a growing body of evidence that these foods aren’t good for us. But experts can’t agree how exactly they affect us or why, and it’s not clear that science is going to give us an answer any time soon.

While recent research shows many pervasive health problems, including cancers, heart disease, obesity and depression are linked to UPFs, there’s no proof, as yet, that they are caused by them.

For example, a recent meeting of the American Society for Nutrition in Chicago was presented with an observational study of more than 500,000 people in the US. It found that those who ate the most UPFs had a roughly 10% greater chance of dying, even accounting for their body-mass index and overall quality of diet.

In recent years, lots of other observational studies have shown a similar link – but that’s not the same as proving that how food is processed causes health problems, or pinning down which aspect of those processes might be to blame.

So how could we get to the truth about ultra-processed food?

The kind of study needed to prove definitively that UPFs cause health problems would be extremely complex, suggests Dr Nerys Astbury, a senior researcher in diet and obesity at Oxford University.

It would need to compare a large number of people on two diets – one high in UPFs and one low in UPFs, but matched exactly for calorie and macronutrient content. This would be fiendishly difficult to actually do.

Participants would need to be kept under lock and key so their food intake could be tightly managed. The study would also need to enrol people with similar diets as a starting point. It would be extremely challenging logistically.

And to counter the possibility that people who eat fewer UPFs might just have healthier lifestyles such as through taking more exercise or getting more sleep, the participants of the groups would need to have very similar habits.

“It would be expensive research, but you could see changes from the diets relatively quickly,” Dr Astbury says.

Funding for this type of research could also be hard to come by. There might be accusations of conflicts of interest, since researchers motivated to run these kind of trials may have an idea of what they want the conclusions to be before they started.

These trials couldn’t last for very long, anyway – too many participants would most likely drop out. It would be impractical to tell hundreds of people to stick to a strict diet for more than a few weeks.

And what could these hypothetical trials really prove, anyway?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDuane Mellor, lead for nutrition and evidence-based medicine at Aston University, says nutrition scientists cannot prove specific foods are good or bad or what effect they have on an individual. They can only show potential benefits or risks.

“The data does not show any more or less,” he says. Claims to the contrary are “poor science”, he says.

Another option would be to look at the effect of common food additives present in UPFs on a lab model of the human gut – which is something scientists are busy doing.

There’s a wider issue, however – the amount of confusion around what actually counts as UPFs.

Generally, they include more than five ingredients, few of which you would find in a typical kitchen cupboard.

Instead, they’re typically made from cheap ingredients such as modified starches, sugars, oils, fats and protein isolates. Then, to make them more appealing to the tastebuds and eyes, flavour enhancers, colours, emulsifiers, sweeteners, and glazing agents are added.

They range from the obvious (sugary breakfast cereals, fizzy drinks, slices of American cheese) to the perhaps more unexpected (supermarket humous, low-fat yoghurts, some mueslis).

And this raises the questions: how helpful is a label that puts chocolate bars in the same league as tofu? Could some UPFs affect us differently to others?

In order to find out more, BBC News spoke to the Brazilian professor who came up with the term “ultra-processed food” in 2010.

Prof Carlos Monteiro also developed the Nova classification system, which ranges from “whole foods” (such as legumes and vegetables) at one end of the spectrum, via “processed culinary ingredients” (such as butter) then “processed foods” (things like tinned tuna and salted nuts) all the way through to UPFs.

The system was developed after obesity in Brazil continued to rise as sugar consumption fell, and Prof Monteiro wondered why. He believes our health is influenced not only by the nutrient content of the food we eat, but also through the industrial processes used to make it and preserve it.

He says he didn’t expect the current huge attention on UPFs but he claims “it’s contributing to a paradigm shift in nutrition science”.

However, many nutritionists say the fear of UPFs is overheated.

Gunter Kuhnle, professor of nutrition and food science at the University of Reading, says the concept is “vague” and the message it sends is “negative”, making people feel confused and scared of food.

It’s true that currently, there’s no concrete evidence that the way food is processed damages our health.

Processing is something we do every day – chopping, boiling and freezing are all processes, and those things aren’t harmful.

And when food is processed at scale by manufacturers, it helps to ensure the food is safe, preserved for longer and that waste is reduced.

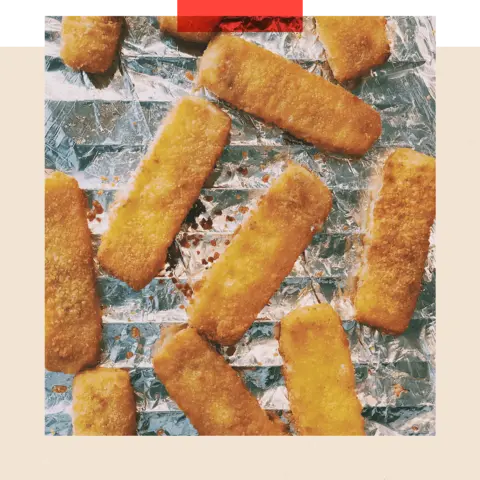

Take frozen fish fingers as an example. They use up leftover bits of fish, provide kids with some healthy food and save parents time – but they still count as UPFs.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAnd what about meat-replacement products such as Quorn? Granted, they don’t look like the original ingredient from which they are made (and therefore fall under the Nova definition of UPFs), but they are seen as healthy and nutritious.

“If you make a cake or brownie at home and compare it with one that comes already in a packet that’s got taste enhancers, do I think there’s any difference between those two foods? No, I don’t,” Dr Astbury tells me.

The body responsible for food safety in England, the Food Standards Agency, acknowledges reports that people who eat a lot of UPFs have a greater risk of heart disease and cancer, but says it won’t take any action on UPFs until there’s evidence of them causing a specific harm.

Last year, the government’s Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition (SACN) looked at the same reports and concluded there were “uncertainties around the quality of evidence available”. It also had some concerns around the practical application of the Nova system in the UK.

For his part, Prof Monteiro is most worried about processes involving intense heat, such as the manufacturing of breakfast cereal flakes and puffs, which he claims “degrade the natural food matrix”.

He points to a small study suggesting this results in loss of nutrients and therefore leaves us feeling less full, meaning we’re more tempted to make up the shortfall with extra calories.

It’s also difficult to ignore the creeping sense of self-righteousness and – whisper it – snobbery around UPFs, which can make people feel guilty for eating them.

Dr Adrian Brown, specialist dietician and senior research fellow at University College London, says demonising one type of food isn’t helpful, especially when what and how we eat is such a complicated issue. “We have to be mindful of the moralisation of food,” he says.

Living a UPF-free life can be expensive – and cooking meals from scratch takes time, effort and planning.

A recent Food Foundation report found that more healthy foods were twice as expensive as less healthy foods per calorie, and the poorest 20% of the UK population would need to spend half their disposable income on food to meet the government’s healthy diet recommendations. It would cost the wealthiest only 11% of theirs.

I asked Prof Monteiro if it’s even possible to live without UPFs.

“The question here should be: is it feasible to stop the growing consumption of UPFs?” he says. “My answer is: it is not easy, but it is possible.”

Many experts say the current traffic light system on food labels (which flags up high, medium and low levels of sugar, fat and salt) is simple and helpful enough as a guide when you’re shopping.

There are smartphone apps now available for the uncertain shopper, such as the Yuka app, with which you can scan a barcode and get a breakdown of how healthy the product is.

And of course there’s the advice you already know – eat more fruit, vegetables, wholegrains and beans, while cutting back on fat and sugary snacks. Sticking to that remains a good idea, whether or not scientists ever prove UPFs are harmful.

BBC InDepth is the new home on the website and app for the best analysis and expertise from our top journalists. Under a distinctive new brand, we’ll bring you fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions, and deep reporting on the biggest issues to help you make sense of a complex world. And we’ll be showcasing thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. We’re starting small but thinking big, and we want to know what you think – you can send us your feedback by clicking on the button below.

Be the first to comment