In 2022, I began curating a queer reading list. It started as therapy homework: I’d been experiencing a lot of shame around my bisexuality — and what better way to unravel that than by normalizing queer experiences via memoir? It was at the tail end of this reading list that an editor suggested Jeanette Winterson’s novel, “Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit.”

I had no idea how impactful the book would be.

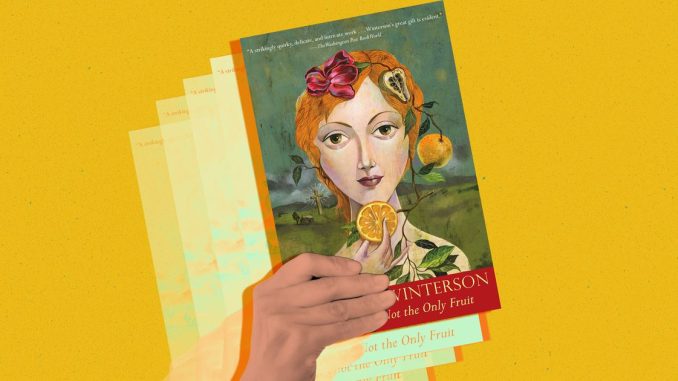

“Oranges,” first published by Pandora Press in the U.K. in 1985, is semi-autobiographical. It chronicles the early life of its protagonist, named Jeanette like the author, a young girl who is adopted by an extremely religious family. As she grows older, Jeanette falls in love with another teenage girl named Melanie, which leads to Jeanette’s eventual falling out with both her church and her mother.

I expected a lot of things when I started the novel. I expected it to be sapphic. I also expected it to be good; the novel was a classic, and it had won an award. On top of that, it inspired a BBC TV show, which won awards of its own.

But I didn’t think it would feel culturally relevant in 2023. After all, it had been written nearly 40 years ago, during the AIDS epidemic. Certainly things had changed since then.

What I wasn’t expecting was the protagonist’s fearlessness — and the way it would stick with me for weeks.

In one particularly tense scene, Jeanette and Melanie are accosted in front of their congregation. They’re accused of sinning together, and the pastor demands that they publicly renounce their relationship.

Melanie recants; Jeanette refuses.

In the following tumult, Jeanette remains firm: Her love for Melanie is pure and good. Jeanette feels strongly enough about this that she retorts to the pastor that he — and the church he represents — are the real problem: “It’s you,” she announces during the service, “not us.”

Jeanette never wavers in this belief. Not during her exorcism. Not during her subsequent starvation. Not even when she realizes that she’ll have to leave her mother’s home, at only 16 years old.

Jeanette’s certainty is breathtaking. It’s poignant and powerful — and it left me unsettled.

I was struck, at first, by how easily Jeanette publicly defended her relationship with Melanie. In the church scene, I’d expected inner uncertainty, or maybe panic, as Jeanette’s orthodox upbringing clashed with what the Grove Press book jacket calls “her unorthodox sexuality.” I expected her to waver, or maybe even default, briefly, to her religious upbringing.

But she didn’t. And that drew out an ugly truth in me: If my own sexuality were challenged, would I be Jeanette or Melanie? With all eyes on me, would I deny my bisexuality out of self-preservation?

That I couldn’t immediately say “No, never,” left me wondering if I was a bad queer.

Before “Oranges,” I had been feeling good about my progress. I was very slowly unspooling 30 years of internalized heteronormativity. I’d been steeped in it, but I didn’t have to stay in it, and by the time I read “Oranges,” I no longer stammered my way through saying, “Oh, I’m bi.” I even began using sexuality labels in my writing bios.

But despite that forward movement, I could still feel my old shame around sexuality lurking about. I was afraid of a public reckoning like Jeanette’s. Never mind that her situation was terrifying, and that it was totally legitimate to feel fear; I’d decided, without meaning to, that being afraid took away from the progress I’d made.

Therefore, I was a bad queer, and I deserved to feel bad.

That wasn’t true, of course, but in the moment, all I heard was: shouldn’t, shouldn’t, shouldn’t. I shouldn’t be afraid of a public reckoning. I shouldn’t have hesitated to say I’d be Jeanette. I shouldn’t have ever been ashamed of my sexuality. All those shouldn’ts put me right back in the shame I’d wanted to dismantle in the first place.

There’s a lot of research on shame. Luckily, there’s also a lot on overcoming it. Dr. Brené Brown, for one, recommends empathy. Similarly, Kara Loewentheil, a lawyer turned feminist life coach, recommends compassion and exposure. Dr. Cathy O’Neil’s 2022 book “The Shame Machine” suggests examining the power structures that benefit from our personal shame(s) to better understand our individual struggles.

I wasn’t ready for any of that, at first. Still impressed by Jeanette’s conviction, and still a little jealous of it, it took me a week or so to process what I was feeling. Only when I started to journal about it did it hit me: I wasn’t a bad queer. And “Oranges” hadn’t set me back; it had given me a new window into my thoughts and beliefs — and wasn’t that what all the best books did?

I now had the opportunity to decide who I wanted to be. Did I want to be like Jeanette? Did I want to be the sort of person who wasn’t afraid of their sexuality, even in the face of shame and public disapproval?

The answer, for me, was yes.

To be clear, whether I publicly discuss my sexuality or not, I’m still a “real” queer. I’m worthy of love and acceptance and validation. It’s OK that I don’t feel as simply as Jeanette does — for one, I’m not Jeanette.

But perhaps more important: Jeanette is a fictional character. Even if “Oranges” is semi-autobiographical, her certainty is an authorial choice. Expecting myself to be as unwavering as a fictional character is unrealistic at best, and damaging at worst.

“Oranges” let me examine my life through a new lens. It reaffirmed my desire to study and discuss both sexuality as a field as well as my own individual orientation. The novel subverted my initial expectation of its antiquity, and it helped me think critically about who I want to be.

For that, I’m very glad to have read it. It’s just as relevant now as it was in 1985.

Be the first to comment